Grape Growing and Wine Making in California in 1859

[Reprinted from California Culturist 1859 “from the manuscript of the Agricultural Society’s Report for 1858” A. Haraszthy. Buena Vista, Sonoma County, February 21st, 1858.]

The Early History of the Vine Culture in California. — The grape vine was brought to California by the Catholic priests in the year 1740 or thereabout, and was planted at the Mission San Diego and Mission Viecho, situated about sixty miles from San Diego in Lower California. Tradition says that said grape vines and olive trees were brought at one and the same time from Spain. Our modern California grapes were, to all appearances, multiplied from these vines, set out originally in the above named places. It is certain that no other variety than this one can be discovered among the native vines at the present age, and it is almost impossible that if several varieties had been imported at that period, they would have so completely run out as to leave no marks of distinction whatever.

The priests and native Californians planted vines in small patches for their own use only, without regard to locality or a view of improving the vine.

Their mode of making the wine — also still in use with some — was to pick the grapes, crush them with the feet, which was the business of a big Indian, put the whole mass in raw ox hides, made sack fashion, for want of barrels; if barrels could be procured they used them also; and after the fermentation, to draw the wine in them, or very often in hides sewed together, water tight. If they made white wine, they squeezed the juice out of the crushed grapes, and put up said juice without the stems and husks for fermentation. From the balance they made their aguardiente, by putting stems and husks together in the still. Brandy was not made until later.

The priests multiplied their vines by planting from the above named Missions the cuttings through all California. It is said that the wine made at the Sonoma Mission was considered by the Padres the best wine made in California, and the priest here had to send to his superiors living lower down some of the wine for their especial use, though they raised more wines at those Missions than at this small Mission here. For the above, my authority is General Vallejo, who has had a vineyard many years since, and annually extends his vineyard considerably.

I annex here the amount of vines in California up to 1858, extracted from the State Register. I may add here that, according to good and reliable authority, the whole number of vines will this winter be doubled. Sonoma Valley has set out alone over 400,000 vines this winter. The Register gives Sonoma and Mendocino counties, in 1858, only 87,621 vines; this must be an error in printing, and should say 187,621, as I myself planted over 80,000 vines last year.

By this amount given in the Register, the yield of wine in 1860 should not fall short of 9,000,000 of gallons, and 400,000 gallons of brandy. [The table will be found in the State Register for 1859, p. 243.] The increase from 1856 to 1858 was, therefore, a little over 263 per cent., and the arrangements made for this season will surely increase the present stock to six millions, if not more.

Climate. — The California climate, with the exception of the sea coast, especially where the prevailing western winds drive the fogs over the locality, is eminently adapted for the culture of grape vines, and it is proved conclusively that no European locality can equal, within two hundred per cent., its productiveness. The oldest inhabitants have no recollection of a failure in the crop of grapes. The production is fabulous, and there is no doubt in my mind that before long there will be, accidentally, localities discovered which will produce as noble wines as Hungary, Spain, France or Germany, ever have produced. Vineyards planted in various counties, from San Diego to Shasta, have proved magnificent results, and leave no doubt in the mind that the north is as favorable and productive as the south.

Locality. — In California, locality is not so material as in European countries, especially where, during the summer season, a good deal of rain falls. If the vineyard is not exposed during the whole day to the sun, said rain will rot and damage the grapes. California having an even temperature, is warm, and without rains in summer, almost any locality will do ; but if a gentle western slope can be obtained, by all means it should be taken.

Soil. — “When the planter resolves to plant a vineyard, he should determine whether he is planting to produce grapes for wine or for the market. If for the former, he must look for a soil which is made by volcanic eruptions, containing red clay and soft rocks, which will decay by exposure to the air. The more magnesia, lime or chalk the soil contains, so much the better. This kind of soil never cracks, and keeps the moisture during the summer admirably. Such soil will produce a wine that will keep good for fifty or one hundred years, and improve annually, is not liable to get sour, or, when exposed to the air, after one year old, to get turbid and change color in the bottle or glass.

If such soil cannot be got on the ground desired to be laid out for a vineyard, the second best may be taken, which is a shell-mound. There are many localities in this state, even as high as the mountain tops, where acres of land consist of decayed shells. Such soils will give a good wine in great abundance.

The next best to the above soil is a gravelly clay, slightly mixed with sand, so that it will not bake. If it cannot be red color, dark black ; but avoid gray clay, which bakes in summer.

The last of all which may be used for the production of wine, is a light, sandy, gravelly soil. This will give an abundance of wine, but it will not keep for any length of time. It will soon change color and become sour when exposed to the air, and the only mode of keeping this kind of wine for years is by adding brandy or alcohol to it, which, of course, deprives it of its purity, and makes the same injurious to the health of the consumer. The soils described above are recommended for producing wine as above stated, but for producing marketable table grapes the planter should select a piece of ground which is a rich, black, gravelly, or sandy loam, exceedingly mellow, as most of the alluvials are; and if well rotten manure from sheep or cattle corrals can be obtained, it will pay well to haul it on the ground. To be prepared for the grape vines it should be moderately moist, though not too much.” In this state often, deserted Indian villages are found ; in such localities the soil is exceedingly rich; a bucket full of it in the hole of a vine will astonish the planter by its effect. Such soils as just now described, either made by nature or artificially, will produce magnificent bunches of grapes, with large berries in an immense quantity, which, of course, will please the eye and palate, as the bulb or skin is thin, and consequently the best qualified for table use.

Plowing. — The best mode to plow the land is with the so-called deep tiller, for with it, by putting three horses abreast, you can plow twelve inches deep, except the soil should be very rocky. Follow this plow in the same furrow with a common shovel plow, or, as it is called in some places, bull tongue. This simple instrument, with two horses attached to it, will tear up and pulverize the earth ten or twelve inches more in depth. There are various designs of subsoil plows, bnt most of them require a great moving power, and will not answer after all. The above named bull tongue is successfully used by many planters in Sonoma and Napa valleys, but it matters very little what plows or subsoilers the planter uses, as long as he plows and subsoils his land from twenty to twenty-four inches.

Laying out the Vineyard. — It is sufficiently proved, by close observations in Europe and California, that the vine planted eight feet apart is the best mode, especially in California, where land is yet cheap and labor high. Vines planted the above named distance can be worked with the shovel plow and one horse. Eight feet is as close as persons ought to plant ; if planted closer the vines, when five or six years old, will branch out considerably, and in the months of May, June and July, it would break all the tender vines by using a horse and shovel plow. The planter would be therefore compelled to employ hands with hoes, and this would cost, in the first instance, ten times as much as horse power ; and secondly, it would not do as good work, for no man will hoe as deep as a shovel plow goes.

Persons laying out vineyards must not be miserly, but leave wide roads, say twelve feet, at least one road every fifteen rows, which would be one hundred and twenty feet apart; otherwise, when the vines bear, and the grapes are picked, the person picking the same must carry a heavy basket a long distance, to the road where the cart stands, to haul it to the press-house. In reality, no person will lose anything on the crops on account of the road, for the rows adjoining each side of the road will bear more, as they have an additional four feet of ground to feed on. No planter should, under any circumstances, plant trees of any description in a vineyard. A vineyard must be a vineyard, and nothing else! I need not waste room here to say how to lay out the rows; every man knows that, and has his own mode for it; but a straight row in every direction is essential to a prosperous cultivation.

Digging Holes. — When the land is laid out, as above recommended, and a stick stuck at every point where a vine is to be planted, a hole must be dug, twenty inches square and about two feet deep. The ground from said hole is to be laid as follows: The top ground to your right, the second ground to the left, and the third in front of the hole; then the bottom of the hole should be well dug up with the spade, leaving the last ground in the hole. The earlier the holes are thus finished before planting the better; then the longer the earth is exposed to the atmosphere and rains, the more it will be fertilized.

Planting. — There are two ways of planting — one with cuttings, and the other with one year old vines. There is a good deal of difference of opinion amongst good and practical vine-planters. Some argue that if a cutting is properly planted at once on the spot of its destination that it will be more advanced in its third year, and, consequently, it will bear in said year more than the rooted vine, which first is set as a cutting in the nursery, and the next year transplanted on its destined spot. It is reasonable to suppose this to be the case, but it still leaves a doubt in the mind whether a larger tract of land can be or will be as well worked as a small one. In a nursery, by good care, the cuttings can be rooted four times as strong as in a large field; besides, in the latter case, whether the vine has good roots or not, it is left where first planted; but when the rooted vines are taken out of the nursery for transplanting the planter will select only those having faultless roots. But the greatest advantage of the nursery is, in my opinion, the fact that if the planter intends to plant one hundred acres of vineyard with cuttings he will have to cultivate one hundred acres during the summer; but if he plants his cuttings for said one hundred acres in a nursery, two acres of ground will be enough to raise sixty-eight thousand rooted vines, the number required for one hundred acres. Now, to cultivate these two acres in the nursery, it will require ten days’ labor, with one horse; while, on the contrary, for one hundred acres, during the months of March, April, May, June and July (after that time no more plowing is required,) you need two men and four horses — equal to two hundred and sixty days’ work, and double that for the teams — then the board of the men and feed for the horses during that period. However, this is a matter of opinion, and each planter will follow his own idea, or will accommodate himself to surrounding circumstances. But now to the planting.

“When the holes are filled as above described, if you plant cuttings, have said cuttings two feet long, bend the cuttings ten inches deep in the hole near to a right angle, the lower part of which is laid horizontally on the bottom, and the upper part on the side wall of your hole, the top of it to be above ground three inches ; then fill the hole from the ground surrounding the hole, which, of course, is top ground; tramp then the earth fast on your cutting that no vacancy shall remain in the hole, otherwise foul air will gather in said vacancy and the cutting become moldy and will not live. But if you plant rooted vines, your holes will be filled to six inches. Now, take your rooted vine, spread the roots on the bottom, and throw from the surrounding top ground on the root, shake it well so that the pulverized ground shall get amongst said roots, then tread gently with your foot around the root. It is still better if you prepare from one part of fresh cow manure and three parts of black earth with water, a mud mixture of the consistency of tar. Before planting, put your rooted vines in the same, and when so dipped, turn them in the bucket round and round; by this every root and fiber of said vines will be surrounded with this tar-like stuff, and prevent the same becoming moldy under ground. After this the ground in front of the hole — taken out the last of the same — is to be leveled so about the vine as to leave a dish-like excavation around the same, as a receptable and conductor of moisture to the roots. Be careful never to plant your vines too deep. It is

better if you make a mistake to have them two shallow than too deep.

Cultivating. — The vines having been planted either as cuttings or as rooted vines, in the month of January, the ground being recently plowed, not many weeds will be visible before the month of March; but this month it will be time to commence, either on account of weeds, or that the ground has already hardened around the vines, and required stirring and pulverizing so that the atmosphere may penetrate freely to the roots; for this purpose the well known shovel-plow is the best and most simple instrument, used commonly in the Western states to cultivate the Indian corn. This requires one horse and a man — said plow can go within an inch of the vines, and consequently destroys all weeds. First, the plowman plows one way, and then, when done with the field thus, he plows crossways; by which operation any weeds escaping the first plow, will be successfully destroyed without using a hand hoe. In this way, one man with two horses — one horse in the forenoon and the other in the afternoon — will comfortably plow three acres a day, as an average, in twenty-six working days of the month.

All plantations of vines, one or more years old, ought to be plowed twice a month, as above described, to keep weeds down, and stir up and pulverize the ground, by which you will charge it with nitrogen. This exposure of alternate strata of earth to the action of the sun, air and rain, fertilizes the soil incredibly; besides the weeds plowed under ground, by their rotting, enrich the earth and impregnate the same with ammonia and humus; then a mellow ground is much more adapted to attract moisture from the atmosphere than a hard caked one.

Pruning, First Year. — When the last plowing with the end of July is done, nothing more in the way of cultivation is necessary until the end of December or beginning of January — the time for the pruning. Your vines, if planted as cuttings, will have but a small shoot; but if rooted vines, these shoots will be strong, and several of them; in either case you cut the vine back to two eyes, always careful that all ground shoots shall be clean cut away from the main stem; your pruning knife must be sharp, so as to make a sound and round cut, to heal eaiser than long cuts that injure the vine; and it looks bad, besides, to see dry sticks of an inch and over sticking out. When the vine sprouts, which is about the month of March, and sooner in this country, the planter must inspect carefully his new vines, and break all sprouts out from the vine except the two coming from the two eyes left for that purpose. This done, the planter must again put his shovel plow to work, and cultivate the soil precisely in the same way as last year, described above.

Pruning, Second Year. — Again, with the end of December the pruning begins, there having been two vines raised on each stem; the one the most feeble or crooked is cut off with the pruning knife; the other is left to the length the planter wishes to raise his vine stem. If it is a small vineyard, I would advise to raise the vine to four feet above ground, and stake it; but with a large vineyard this would be too expensive in this country, and then to cut your vines to two feet and a half above ground. If sticks are to be used, they are to be driven in the ground after the vines are pruned; if not, then these stems, cut to the hight of two and a half feet, should remain as they are for the present. When the sprouts begin to show themselves, the vines must be thoroughly cleaned from them, and every bud rubbed off on the vine except the three top buds, which are left to make the head of the stem, but besides these nothing must be tolerated to grow on your stem. The shovel plow is now put to work again as in previous years: this time the planter will have a small crop, several pounds of grapes to the vine, but must mind if vine is bearing too much; break this surplus out in the beginning, as it would enfeeble your yet tender vines, and be injurious to them for coming years.

Pruning, Third Year. — The grapes having been gathered, the pruning will begin again, and in December or the beginning of January, this time there are three vines on the main stem; two of these vines must be cut to two buds each for making wood — for so-called water branches or vines — to become, the next year, the bearing vines; and the third one of these vines cut to four buds, which will be quite sufficient to bear grapes, but if the main stem is quite thrifty you may have five buds; such a vine will average, in this country, generally, from ten to fifteen pounds, and often as high as thirty pounds of grapes. After said pruning the cultivation goes on as in the preceding year.

Pruning, Fourth and Subsequent Years. — Many and various are the opinions in pruning bearing vines. Some assert that the old way, to cut the vine back to from six to ten spurs, and on each spur to leave two or three buds is the best; but on mature reflection, considering that the stem so cut has to make all the wood, besides to produce and ripen the grapes, it is not reasonable to believe this mode to be correct; and in fact, experiments in different countries and climates have proved this doctrine false. It is a well established fact that the best mode of pruning is to cut the stem to three spurs each, with two buds, and leave three vines each two or three feet long, according to the strength of your stem; the three spurs will grow this year wood for next year’s bearing, and the long vines will grow the grapes. Next season the old three vines which have borne grapes this year, are cut off to spurs with two buds each, and the three vines originating from the last year’s spurs are left to bear grapes this year, and so on alternately from year to year. This mode of pinning will insure a large crop every year, and will not exhaust the vine.

Summer Pruning. — The native Californians never used to prune vines in the summer, but let them grow any length they pleased. This is erroneous; every person on reflecting at once can see that the sap required to grow and produce vines ten, and often twenty feet long may be better used if it is forced into the grape; undoubtedly the berries and bunches will be large, if moderately trimmed; besides, this trimming is a great advantage when the grapes are gathered, as the picking is so much easier than in an untrimmed vineyard where everything is tangled up. The best mode is to cut the tops of the vines to the height of five or six feet from the ground, in the month of July, for the first time, and the second time in the middle of August. This operation is done easily and pretty quick; one man with a sickle tops off about 2,500 a day. Besides the above named advantages there is one more, viz: where the top is cut off, everywhere small vines will spring out and form a dense leaf on the ends of said vines, keeping the grapes growing underneath in a moderate shade, and thus making them more tender, juicy and sweeter. It is, therefore, a mistake, practiced often by new comers from modern Europe, that they will break out the so-called suckers — that is, little branches starting out behind the leaf and growing feebly up to the length of a few inches. These, in the northern part of Europe are broken up, but not in Italy, Greece, Smyrna, etc. Now California, having a warmer climate, the vines need more protection against the sun than elsewhere ; and experience shows, that where some bunches of grapes are exposed without the shelter of their leaves to the rays of the sun, the berries remain small, green, hard and sour.

Age op the Vine. — This depends on its treatment by pruning, distance of the vines from each other, and the climate. In France a vineyard, planted two and a half to three feet apart and two feet in the rows, and of course, trimmed spur fashion, will be very feeble when twenty years old, and as to its yield almost worthless. If planted a larger distance apart and pruned in the alternative mode — that is, short spurs for wood and longer vines for bearing — it will be at thirty or more years pretty good yet.

In the upper part of Hungary, closely planted and badly trimmed vines, last from fifteen to twenty years only; in the southern parts of Hungary, from twenty-five to thirty years; in Italy, Greece, Smyrna, etc., where the close planting is not in custom, the vines reach an age from one hundred to two hundred and three hundred years, and will bear every year a crop from 1,000 to 2,000, even up to 4,000 bunches of the largest size.

California seems to possess even more power of keeping the grape vine during a long period of years in vigor, notwithstanding said injudicious trimming. There are Missions in southern California where vines are eighty years old, and with good care, will last treble and quadruple that amount of time. I believe that a vineyard planted eight feet square to the stem and pruned on the alternative system will last three hundred years and be vigorous in its bearing.

In general, no manure is or was used by native Californians on their vines; there may have been an exception of one or two persons, but not to my knowledge; and of course, the new settlers have no occasion as yet to manure their new plantations, which are still rich enough without it.

Gathering the Grapes. — No grapes ought to be gathered for making wine until they are ripe, and in fact over ripe. As long as they do not stick, when handled, to your fingers, like sirup or honey, they are not fit to make a genenous wine. Some persons hurry on the vintage, in fear that the frost will hurt the crop. This is erroneous; the frost improves the ripened grapes, and makes the wine far superior to that of grapes gathered before the frost. The world-renowned king of the wines, as the Tokay is called, is made in Hungary, from grapes gathered very often under the snow, and never before a good frost has shriveled them.

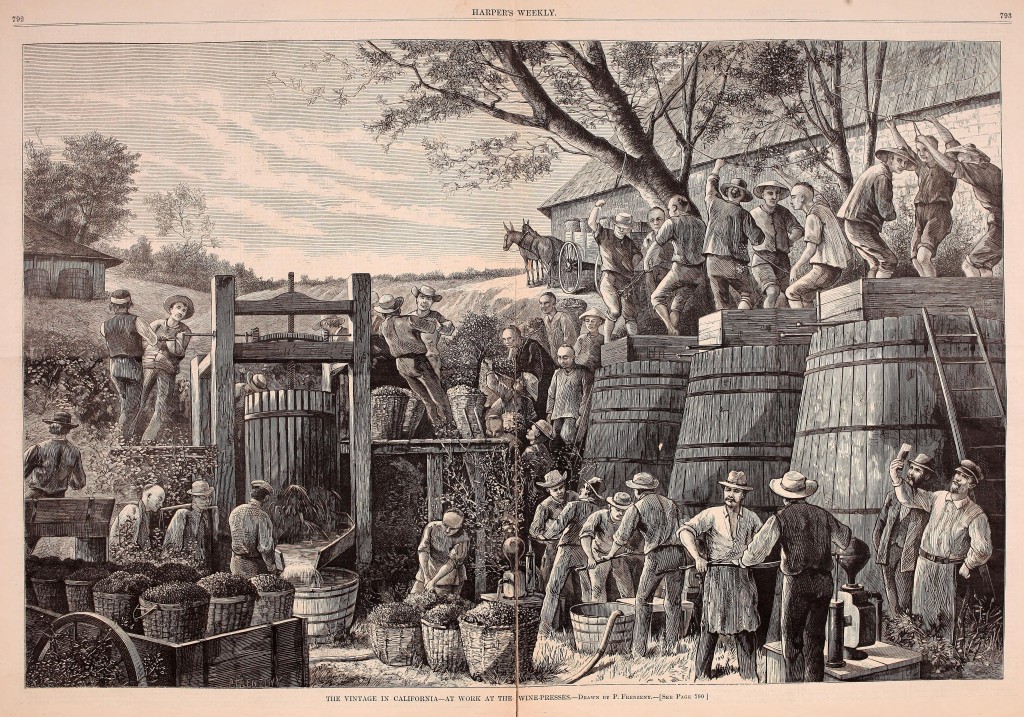

The gathering is simple and expeditious. One man with a basket can gather from 1,500 to 2,000 pounds of grapes a day in this country, if there is a cart close by to take the grapes to the press, provided the vines are summer pruned and not entangled.

Persons having small vineyards will do well to gather their grapes in the morning, and not later than nine o’clock; for if gathered in the heat of the day, the fermentation will be too vehement, which is not good for making the best of wines; but when the vineyard is large, other remedies must be employed to prevent a too hasty fermentation.

Crusher. — When the picked grapes are brought to the press house, they ought to be crushed immediately, and not left standing in tubs over night, or the next day. The crusher is a simple machine: there are three cast iron cylinders; two of them of even size roll against each other ; the third one is on top of the two lower ones, and is fluted for the purpose to take hold of the bunch and jam it down to the two lower ones; these latter have very small projections, like a waffle-iron, so as to crush the grapes, but not the grape seed, which would be injurious to the taste of the wine.

I have one of the above named crushers, made to crush apples for cider, and it answers admirably. Two men can crush with it 5,000 pounds of grapes easy in a day.

This crusher is placed above a common screw press, in which the grapes from the crusher will fall, with stems, juice, and seed ; the juice running slowly off by itself, and is carried in buckets to the cellar, and filled in the barrels.

Press. — This instrument may be made simple and almost to every man’s own idea or taste; it is not material, as long as it presses out the juice of the grapes. The top planks are placed on the substance and the screws drawn to squeeze out the juice from said crushed grapes.

White Wine. — It was mentioned before, that during the crushing of the grapes and falling of the same in the press, some juice will run off without pressing; this juice will make the first quality of white wine, and is generally barreled by itself. When the press becomes full, and is pressed slightly, the juice thus gained will make the second quality. Now the balance remaining can be used to distill brandy from, or make an inferior quality of red wine. For the latter purpose, put the whole mass, with stems and all, into a large fermenting tub, and when nearly full, fill the balance with pure water and let it ferment.

The first and second run of the juice, as stated, is put in separate barrels, which are filled within six inches from the top, the bunghole covered with vine leaves or a cloth, and left for fermentation.

Red Wine. — If persons wish to make first quality of red wine, the process is as follows:

Crush your grapes as above stated ; take the whole crushed mass together, with its juice, and put it in the fermenting tub; cover said tub with a clean cloth; let it ferment in warm weather six days; if cool, twelve or fourteen days, and take every day a crutch-like stick and press the stems, which will come to the top of your tub, down into the fluid mass; when, after the above given time, you put your ear to the tub and hear no fermentation, the wine is ready to be drawn; but to be perfectly sure, take a gimblet and bore a hole in the tub about from six to ten inches from the bottom, according to the size of the vessel, and if the wine comes out clear you can draw it off into the barrels; but in your fermenting tub you must have, previous to putting in the mass, nailed a grate or kind of sieve over the faucet hole, to prevent the grape seeds from coming into the faucet hole. Now your red wine barrels have to receive the same care, as stated above of the white wine, in your cellar, with the exception that the red wine barrels must be filled full, as there is no danger of a strong fermentation as of the white wine. Of course every person will understand that to make red wine you must have blue grapes; but white wine can be made as well from blue as white grapes.

Second quality of Red Wine. — It was stated above that the white wine from the blue grapes was pressed, and then the mass of stems and husks was put into a fermenting tub filled with water and left for fermentation, the fluid drawn off thus would give only a poor wine; but if said fluid is pressed over stems and husks in a second tub, and left over them for twenty-four hours, then drawn off and poured over stems and husks in a third tub, and this way continued up to five or six tubs — the fluid drawn off from the last tub will make an excellent wine the next July or August.

When the fluid from tub number one is drawn off to pour it over the stem and husk mash in tub number two, one must be filled with warm water, which is left twenty-four hours on it, and then the same process is applied as above described — said fluid passing through all the tubs ; and this is to be continued by pouring slowly warm water over the masses in said tubs until every particle of spirituous matter is extracted from them — this so extracted fluid is then used to distill brandy from.

Barrels. — Nothing in making wine will require more attention and watchfulness than the keeping of the barrels clean. The planter may have the finest locality, the best soil, and good ripe grapes, etc., and still his wine will have a bad taste, become sour, turbid and unpalatable, if he does not take the best care of his barrels. He is often compelled to purchase all sorts of barrels, and may think, by putting hot water in the barrel and washing it out several times, it will be fit for use, but this is a great mistake; then such barrels are mostly moldy and sour; neither the first nor the latter will be removed thus; but only if the head of the barrel is taken out, and the barrel itself thoroughly burnt out with shavings or straw, so that its inner parts be charred from one-sixteenth to one-eighth part of an inch all over; then washed out first with hot and last with cold water several times until the same runs off clear, the barrel will become sweet.

The above process is with barrels which the planter has purchased, or such of his own that become sour or moldy by neglecting the precaution I will give forthwith, viz: When your wine barrel gets empty, take said barrel immediately and wash it out with hot water, then several times with cold water, and burn some sulphur in it in the following manner:

1st. Put the spigot air-tight in its hole.

2d. Have the bung covered, with a clean linen rag also in readiness lying next the bunghole.

3d. Make a small hole in your sulphur-coated linen strip.

4th. Insert into this hole a piece of wire one or two feet long.

5th. Light said sulphur strip and push it quickly through the bunghole into the barrel and bung it up.

As long as an oxygenous air is in the barrel the sulphur will burn, and fill with its fumes the barrel; when extinguished, take said wire out and bung up the barrel air-tight, and keep in a dry, sheltered place, ready for use. A barrel prepared in this way will never sour or become moldy; and when you intend to fill the same with wine, you have only to wash it out first with hot and then with cold water. Said sulphur strips can be got in some stores, but each planter may prepare them for himself by melting the sulphur and dipping them into the molten mass.

Press House. — This building should be invariably in front of the cellar, as otherwise it would be inconvenient to transport the wine, and juice pressed out, from the fermenting tubs and the wine press to the barrels in the cellar. In large vineyards the press house ought to be two stories high, so as to have the barrels in the cellar filled by means of hose — to save wine and labor — at once, without any spilling, etc. In said press house there should be sufficient room for the press, the crusher, the fermenting tubs, all the empty barrels, and other articles necessary for manufacturing the wine.

Cellar. — If the planter has a mountain convenient, which consists of soft stone or clay, the best mode is to make the cellar in the mountain; the length, of course, depends upon the size of the vineyard, the width upon the quality of the rock or clay; if strong, you may venture twenty feet; but if not safe to that width, make it thirteen feet, with a Gothic arch. This kind of a cellar is very cheap — much more so than a farm barn — is perfectly secure against fire, and makes excellent wine. Then a good cellar, with an even temperature during the whole year, is a material requisite for producing good wine. If there should be no mountain close and handy, the next best way is, when rocks can be had, to dig in the ground six or eight feet, begin two walls thirteen feet in the clear, and draw them gradually to a Gothic arch; when closed, cover these rocks several feet, with the ground dug out of the place, and it will give you an excellent cellar — strong, and of nearly an even temperature. Almost any man who can lay a stone fence can make such a cellar. But if no rocks can be had in the neighborhood, build a thick wall with adobes, two feet thick; make it seven feet high; put heavy redwood beams on the top of the wall; cover it with redwood planks, and throw one foot of mud upon them; then cover the whole with a shingle roof. A slight ventilation is beneficial for the preservation of the barrels, and a pure air to prevent mold.

The cellar and press house should be kept very clean; no stuff which may rot or get sour should be tolerated in them or near by, as wine quickly attracts all bad smells and acidity.

Treatment of Wines. — When the -white wine is thoroughly fermented in the barrel, and become clear, it has to be drawn into another clean and, previous to filling it, sulphurated barrel ; of course, white wine is put in a barrel which contained before white wine, or was charred recently. Keep the barrels always well filled. At least every fortnight (better once a week) have them cleaned at the bung hole, of the so-called wine-flower, and filled up with the same kind of wine, or even with better, but never with inferior stuff. In the first months it will take more wine to fill the barrels than towards the end of the year.

If you have a barrel (as we call) on the faucet, from which wine is drawn from time to time, or daily, when such a barrel becomes a quarter or more vacant, put a small sulphur brand in the same, first to prevent your wine being partly transmuted into vinegar ; and second, that said empty place in your barrel shall not become moldy, and spoil the succeeding wine, or have to be unheaded, and charred anew.

Making California Tokay. — This noble wine, which I have made in California with good success, is produced as follows:

Select your best and ripest grapes, place them upon straw mats, or cloths, under some shady place — -let them be there for some four or five weeks — when they are well shriveled, or half dry, you pick out every rotten berry; then put about one hundred pounds in a bag, made from common coffee-bag stuff; hang the bag up, and place some vessel under it, to collect the droppings by its own weight, often turning said grapes in the bag with the hand; when it stops dropping, empty the bag in the crushing machine, crush the grapes, and press the juice out of them; give both kinds separate barrels to ferment in, and designate the same with number one and number two, viz: the pressed juice will give the second quality of tokay, and the other first quality. Observe in its treatment the rules above given, and you will have an excellent tokay-like wine, but it will require from three to four years before it is fit for market.

Making Champagne. — For this quality of wine it seems the Sonoma Yalley is peculiarly well adapted, as our white wine, even if not manufactured into champagne, possesses a taste similar to the champagnes that have stood some time in a tumbler, or open bottle, and it makes an excellent article, though combined with a great deal of labor.

1st. The grapes destined for champagne must be over ripe, sticking to the fingers, as above mentioned; they must be gathered on a frosty or very cold morning, early — if possible, before the sun rises — put in a sack of strong linen, and by twisting it the best juice is pressed from the grapes, leaving the balance for common wine; fill with this still cold juice your clean, well sulphurated barrel, half full only; put a long bung into it, strongly guarded with such a filling that may be easily removed without disturbing the fluid in the barrel when you extract the bung; secure, also, the headings of the barrel, that the gaseous matters of the fermentation shall not force them out, and leave it in this state, undisturbed, until February or March; then carefully open the bung, that the fluid shall not stir up the sediments; put in a syphon, but mind that said syphon shall not reach as low as the settlings, and draw the clear fluid in a clean barrel, with a stop-cock, and from there into the bottles, each bottle to receive first one spoonful of powdered candy-sugar and a spoonful of the best and purest spirits-of-wine; cork the bottles with a corking machine, purposely made for it; tie the cork down with a strong hemp twine, then lay your bottles on their sides, so that the cork is always kept in the fluid; the bottles must be for several months, from time to time, handled, to regulate the fermentation; if too slow, they must be put in a warmer place; if too strong, in a cooler one; then, if not well regulated thus, the bottles will burst by hundreds; and, with the utmost care, about five per cent, of them is lost. The bottles must, in this way, be handled twice every week, and gradually raised on the bottom, so that they become more and more perpendicularly standing on their neck, so that the sediment will settle on the cork, and leave the balance of the wine perfectly clear, which the practical eye of the champagne-maker will soon discover; then the bottle is taken, by one well trained for this task, in his left hand, carefully, not to disturb the wine, while his companion cuts the twine, and taking hold with his right on the cork, he lets the same sidewise slide out, to leave, for a moment only, a small aperture, of which about a teaspoonful can escape into a basin, over which he holds the inclined bottle, and immediately presses the cork back to its former position, and holds it there fast until his partner ties it with a strong hemp twine, which, lastly, is yet strengthened with a copper wire. By this operation the settlings on the cork are ejected, with great force, in a moment, and leave the wine entirely crystal-like. That, for this operation, a well practiced hand is needed, every one will percieve. I would, therefore, not recommend the attempt to make champagne for market, as this is a trade by itself, and in large wine establishments, where they make the champagne, every man has his own duty or office to perform; one fills, another corks them, another lets the settlings blow out, etc. But the above is only given that amateurs may make, for their own use, some bottles of it.

To Make Port Wine. — To make good and superior port wine, take good ripened black grapes, dry them in the sun almost to raisins; when so dried, pick the berries from the stems, crush them, and put them in the fermenting tub. If your grapes are not very sweet, put fifteen pounds of New Orleans sugar to each sixty gallons of said mass, and add to it thirty gallons of one or two years old red wine and two gallons of pure spirits-of-wine; then let the mass slowly ferment. When fermented and clear in the tub, draw it off in barrels, but fill the barrels only two-thirds full; take after this one-third of the liquor, put it in a clean boiler, bring it to a boiling heat, but let it boil up only once; take it from the fire, fill your already two-thirds full barrels within six inches, with the same, and cover the bung-hole with leaves or clean rags; the mass will thus ferment again. In the month of May you may draw the wine in a clean barrel. This will make in a couple of years an elegant port wine.

This treatise being written for the agricultural report, I cannot take too much space in enumerating the making of the various other wines. I will therefore leave that to a more extended work which I intend to publish soon.

Making Brandy. — It was described above, in mentioning the making of the second and third quality of wine, how to extract from the stems and bushes the spirituous parts left in them, with terpid warm water. Take now that so extracted fluid, put the same in your copper still, and distill it over in the same manner as whisky. This first product is then put in a tub with one-fourth pound fresh burned charcoal to the gallon, in a pulverized state, and therein well stirred up for half an hour, and with it again fill your apparatus, and distill it over by a slow fire. If the heat is too strong, you would not only lose on spirit, but your brandy would get weak. In order to make a first-rate article it requires a third distillation. Brandy thus prepared will be superior to most of the imported ones from France, as these are, with very few exceptions, all mixed in France with alcohol, and those which are not, cannot be had here short of twenty dollars a gallon, as these brands are engaged for six dollars and eight dollars there, five and even ten years ahead, by the nobility and rich merchants in Europe. France imports from America, Germany, Hungary, etc., millions of gallons of alcohol for the very purpose of mixing the same with brandy. The product of its vines is constantly decreasing on account of their exhausted soil and their unhealthy condition; while, on the contrary, the demand for brandy is increasing, to supply which they take refuge in the alcohol. This is the case also with the greater part of their claret, which is extracted from the stems and husks with water many a time, to give it a wine taste ; said watery extracts are then mixed with alcohol, sugar, cream-tartar, colored properly, and sent to the United States, to be drank here with great relish as French claret — everybody believing them genuine articles, especially when they buy or have them bought out of the United States

Bonded Warehouse.

To Make Brandy Old. — There are several secrets which are imparted only for very high prices by some celebrated manufacturers in France, and even for so high prices as one thousand ducats. They will only communicate their secret of making superior brandy to such persons as are highly recommended by influential men. But to improve the brandy and give it the so-called mildness, they commonly take it to a warehouse, which is several stories high (from forty to sixty feet) and let it run down from the very top to the bottom, in fine streams as thin as twine, through the trap-door passage, and repeat it several times, thus said brandy will materially gain in mildness, but, of course, will lose in strength. Another method is, to heat pebble-stones and throw them into the brandy barrels, and repeat this monthly, and the brandy will thus improve more rapidly in a year than otherwise in three. Some unscrupulous men even use prussic acid, in a diluted state, to give their brandies the flavor of old brandy, and thus poison the same to the great injury of health and life. The mode to prepare the very finest brandy, in an entirely innocuous way, the writer of this cannot disclose, having been compelled by his teacher, about twenty

years ago, to pledge his word of honor for keeping the secret.

Having said — not all I could — but all that might be properly brought within the compass of a short treatise, concerning the cultivation of vineyards and the making of wines and brandy, I deem it necessary to make a few remarks in regard to the quality of our wines. They are, at present, all made from the native California grapes as our foreign varieties were but few in number to make into wine, especially when some varieties brought from thirty-seven and a half cents up to a dollar, and even a dollar and a half per pound. It is nevertheless certain that grapes of different kinds, off the same soil, well assorted, will make a far superior wine. To illustrate this more to every man’s mind, I will compare the wine-making with the cooking of a vegetable soup. You can make from turnips a vegetable soup, but it will be a poor one; but add to it also potatoes, carrots, onions, cabbages, etc., and you will have a fine soup, delicately flavored. So it will be with your wine; one kind of grapes has but one eminent quality in taste or aroma, but put a judicious assortment of various flavored grapes in your crushing machine, and the different aromas will be blended together and will make a far superior wine to that manufactured from a single sort, however good that one kind may be.

No doubt some of my readers wish to know what sorts would be the best to plant. This is a difficult matter to be decided at present, as it requires some years to determine which quality of the imported species will be the best for this purpose; a great deal, besides, depends on locality and soil. In one soil or locality one kind will thrive and be superior to a kind that will, in another locality or soil, far excel the former. So much I can say from my own experience, for California: that, with few exceptions, my imported vines from Hungary and other parts of Europe, have shown a peculiar preference for our soil or climate, or both together; bearing sooner and larger bunches and berries, than in their native country. Whether this will continue, it is to be proved by the future. Repeated trials have been made by planting the species from the celebrated localities, as Tokay, Johanisberg, etc., in lower parts of Hungary — what are called the lower flat lands or plains — consisting of very rich, light, sandy soils; they bore fine flavored grapes for a few years, but soon lost said quality and made as poor wines as the native vines ; and so the reverse, vines raised in these low lands, when transplanted to those celebrated spots, greatly improved and made good wine. I would recommend all planters to get as many varieties as they can test, and compare their qualities on their own soil, and keep on cultivating those which thrive, bear the most, and make the best wine. This is the surest mode of getting satisfactory results.

Cost of Planting a Vineyard. — This, of course, will vary with the price of labor, locality, and soil ; but to give an idea to persons who have no practical knowledge, I will give a correct account of the planting of a vineyard of one hundred acres. This was actually expended on the same, in labor and money, having kept a strict account of everything. The soil is red clay, intermixed with partly decayed, and partly in the process of decaying, volcanic rocks, the soil having been previously cultivated for grains. These one hundred acres were planted in January, 1858.

| Three teams, three men, nine horses, twenty days with deep tiller; three teams, three men, six horses, twenty days with the shovelplow; six men lining out and staking, twenty-one days; twelve men digging holes, twenty-one days; six men planting, twenty-three days; one hundred and twenty days’ work; wages, $35 per month, board, $15=$50; per day, $1 93 | $231 60 |

| Current prices of horse-hire, fifty cents per day for fifteen horses, $7 50; twenty days’ use | $150 00 |

| Horse-feed, grain and hay, twenty five cents per horse | $75 00 |

| Blacksmith’s bill, wear and tear of harness, etc | $30 00 |

| Eighteen men laying out and digging holes, wages, $30; board, $15; two hundred and seventy-eight days’ work | $653 94 |

| Six men planting, twenty-three days’ work; wages, $30; board, $15; one hundred and thirty-eight days’ work | $238 74 |

| There were thirty-two days’ work spent in digging the rooted vines in the nursery, hauling them and trimming, etc | $55 36 |

| The making of cuttings and planting them in 1857, in the nursery for rooting, their cultivation during summer, did bring these rooted vines to four and a half cents a piece, or 68,000 vines at $2 50 a thousand. | $170 00 |

| Total cost of planting said one hundred acres | $1,604 64 |

| First summer’s cultivation, two hundred and sixty days manual labor, $50 per month, with board | $500 00 |

| Horse-hire, and their feed for five months | $205 00 |

| Blacksmith’s bill, wear and tear of harness, etc, | $15 00 |

| Pruning, first year, in January | $25 00 |

| Total summer work and fall pruning | $745 00 |

| Second Year’s Expenditure. — Replanting those which died out from the years planting and sprouting | $60 00 |

| Summer cultivation, as last year, with fall pruning | $745 00 |

| Second year’s total expenses | $805 00 |

| Third Year’s Expenditure. — Sprouting and additional expense for pruning, as this goes slower this year | $120 00 |

| Summer cultivation, as above | $745 00 |

| Third year’s total expense | $865 00 |

| Total expense up to bearing | $4,019 64 |

The Yield of the Vineyards. — This depends, in a great measure, on the soil, the cultivation and care bestowed upon your vines. I will here give the product of vines planted in my vineyard.

Lot number five contains one thousand, seven hundred and ninety-three vines, planted from cuttings, permanently, in February, 1854; bore, on an average, to the vine, in 1857, nine and a half pounds of good grapes ; in 1848, on an average, forty pounds of grapes. The soil is very rich, and there was some time ago an Indian

village there.

Lot number two contains one thousand, two hundred and thirty-two vines, planted in 1854, with one year’s rooted vines. In this lot the grapes have not been weighed, but an account was kept of the wine made from them. It yielded one thousand, two hundred and sixty-five gallons of the first quality of wine in 1857, and grapes were sold from this lot to the amount of one hundred and five dollars, besides what were used for the house. In 1858, this lot averaged three gallons of wine to the vine. The soil is red clay, of volcanic origin, with decayed rocks.

Lot number one contains one thousand, three hundred and twelve vines, twenty-four years old. Last year the account of the weight of the grapes was lost by accident. No correct average can be given, but this year the average product was eighty pounds to the vine.

In the valley of Sonoma, grapes well cultivated, in good soil, will give one gallon first quality wine from twelve pounds, one-eight gallon of second quality, one-sixteenth gallon of fourth proof good brandy, besides some vinegar.

The wine can be sold young, if made into first quality white -wine, to San Francisco merchants, for seventy-five cents, and second quality red wine for fifty cents per gallon, and new brandy at two dollars and fifty cents. The reader will see by the above that vineyards will pay at the present rate from one to two thousand dollars per acre, according to soil and age of the vines.

Preserving Grapes. — The best mode of preserving grapes is, in my opinion, the following: Build from boards a fruit house, having between them one-eight part of an inch space, instead of joining the boards close together, in order that the air may freely circulate; then put slats up to the top; gather your grapes before they get wet from the rains, which makes them rot and burst easy; tie two bunches at the ends of a piece of twine, a short distance apart, and hang your bunches thus tied up on the slats; mind that the bunches do not touch each other, and your grapes will keep till summer. I have now — February twentieth — as fine and fresh sound grapes as if gathered a week ago.

Being limited in space and time, I must conclude this already too long treatise, but in concluding, I would respectfully suggest, that if the Federal Government would give instructions to the different United States Consuls, living in all parts of the civilized world, and especially to those who live in celebrated wine countries, to collect annually a certain amount of vine-cuttings from all varieties, good and bad, and send them to the Patent Office, the Commissioner of Patents might direct the planting of said cuttings in a congenial soil and climate, and when fairly rooted and multiplied, have them distributed in such parts of the Union wherein vines thrive. The expenditure of the government would be a trifle in comparison with the immense benefit our citizens would derive from it, and it would save, in a few years, millions of dollars that are now sent to foreign countries for wine, brandy and raisins. California, with such aid, would not only produce as noble a wine as any other country on the face of the globe, but it would export more dollars’ worth of wine, brandy and raisins, than it now does of gold. A. Haraszthy. Buena Vista, Sonoma County, February 21st, 1858.