Jeanne Paquin Portrait and Biography – Page 2

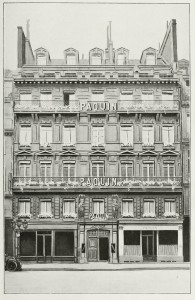

Maison Paquin Rue De La Paix 1909

from La Ville lumiere Published 1909 by Direction et Administration in Paris .

Being thus favourably disposed towards John Bull, she was destined to make his closer acquaintance. The English school of portraiture at the National Gallery has no more ardent admirer than she, and none more appreciative of the innate distinction of those sitters to fashionable brushes. And what documents for the study of dress! There must be different standards of embellishment for the two nations, for face and figure are different. Piquant and picturesque sum up some of the more palpable differences. Englishwomen are not piquant, few French are picturesque; but if our country-women are wanting in “chic,” they make up for it in “race ” and breeding. All this means that the principles of raiment change with the latitude, but the latitude must not be too great! Nowadays there is a levelling up amongst the nations. If Paris leads, London and the other capitals make haste to follow. The dressing of a London crowd is infinitely better than twenty years ago.

These are fascinating topics, but they do not exhaust the conversational powers of Mme Paquin. I know no one more competent than she to give an opinion on most things having relation to the sex. Though one of the most capable women in the world, she is extremely moderate in her Feminism. Just after she was decorated, she remarked to me: “I am glad the Government has recognised my work, independent of my sex; that is as far as my Feminism goes. I do not think women should plunge into every avenue of employment, any more than I think homes will be happier when women discuss politics with tired husbands. The latter can read that sort of thing in the newspaper.”

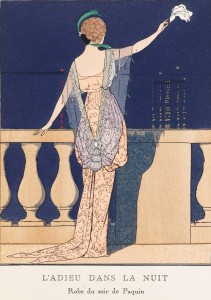

Mme Paquin, you may be sure, has no sympathy with the militant, whom she considers out of harmony with the age – an age of reason and persuasion as opposed to force – notwithstanding the Great War. Nor could any one, knowing her elegance and charm, imagine that she would countenance the crude methods of house-burners and the rest. “Localised madness,” she calls it. Indeed, Feminism has made vast progress everywhere – except in England. After all, this tired old world is more amenable to smiles than hatchets. Even cannon must yield to moral force. In trying to be “serious” the suffragette has become ridiculous. And, really, her strange pranks have merely complicated the question.M. Paquin showed in his life the rare combination of artist and business man. If a great grasp of details is required to run a large commercial concern, talent is likewise needed to evolve a dress. How is it done? It is one of the secrets of the gods. Mme Paquin lifts occasionally the veil in conversation with her friends. The dress designer, she says, is influenced by events – by a new play, a costume ball, a new kind of flower. A sunset may suggest new colours to her palette; the spring-time has its own tender message; old engravings and old masters also inspire the creator of clothes. On days when Mme Paquin is in form she will design five or six new dresses; when the ideas will not come, she abandons the task until the following day.