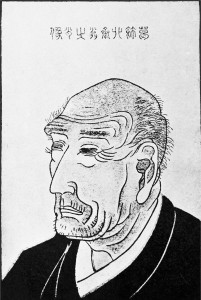

Katsushika Hokusai Biography

BORN: 1760

DIED: 1849

In the autumn of 1760, when Hogarth had just had his Sigismunda thrown on his hands by Sir Richard Grosvenor, a child was born in a humble suburb of Yedo whose place in the world’s art was destined to be at least no less important than that of the English painter of life and character. His parents were of the artisan class; the father a maker of metal mirrors to the court of the Shogun, the mother a member of a family that was not without celebrity in its time, but had lighted upon evil days. Her grandfather had been a retainer of the courtier Kira, in whose defence he had fallen by the hand of one of the forty-seven Ronins during the midnight attack which was the climax of that tragic episode of seventeenth-century Japan. The vassal’s family had been involved in the ruin that overtook the house of his master, so that in the next century it was not strange that his granddaughter should have married a workman. Perhaps to this soldier ancestor we may trace the pride and independence that characterised Hokusai all his life, just as the employment of his father — for Japanese mirrors are decorated on the back as well as polished on the face — might be supposed to influence the child’s tastes and capacity in the direction of art.

Possibly because he was not an only son, he left home when thirteen or fourteen to be apprenticed to an engraver. Though he did not remain at this trade for more than four years, the experience thus gained must have been exceedingly useful to him in after life, when he had to direct the men who were cutting his own work. Some letters on this point to his publishers are not without interest. In one, dated 1836, we read: “I warn the engraver not to add an eyeball underneath when I don’t draw one. As to the noses; these two noses are mine (here he draws a nose in front and in profile). Those they generally engrave are the noses of Utagawa (Toyokuni), which I do not like at all.” Several prints actually engraved by Hokusai are still preserved. At the age of eighteen he left this employment to join the school of the great designer, Shunsho, whose colour prints are among the treasures of modern collectors, where he became an apt imitator of his master’s style. His originality, however, could not long be suppressed. An enthusiasm for the vigorous black and white work of the Kano school irritated the old professor, whose dainty art aimed at very different ideals. At last, in 1786, a quarrel over the painting of a shop sign resulted in the expulsion of the disobedient pupil.

No doubt such an inquisitive, unconventional scholar must have sadly perplexed a master who had long been regarded, and quite rightly, as one of the leaders of the popular school. Yet in those eight years spent under Shunsho’s guidance the younger man must have learned all that was to be learned from Ukiyo-yé art, and no further advance was possible for him until he had gained his freedom.

Thus, at the age of twenty-six, Hokusai was cast adrift upon the world to try to make a living by illustrating comic books, and even writing them. He was attracted for a time by Tosa painting, and worked in imitation of it; but, work as he might, he was unable to make a livelihood. At last in despair he gave up art and turned hawker, selling at first red pepper and then almanacs. One day, as he was crying these latter in the street,his former master, Shunsho, happened to come along. The pride of Hokusai would not allow him to stoop to begging, so he plunged into the crowd to avoid recognition. After some months of misery an unexpected and well-paid commission to paint a flag aroused hope in him once more. Working early and late he succeeded in executing illustrations to a number of novels, and designed many surimono — the dainty cards used for festive occasions—with gradually increasing reputation. It was about this time that he learned, or rather came in contact with, the rules of perspective, and began to catch something of the grandeur of the early art of China.

In the spring of 1804 he made a popular hit by painting a colossal figure in the court of one of the Yedo temples. On a sheet of paper more than eighteen yards long and eleven yards wide, with brooms, tubs of water, and tubs of ink, he worked in the presence of a wondering crowd, sweeping the pigment this way and that. Only by scaling the temple roof could the people view the bust of a famous saint in its entirety. “The arch of the mouth was like a gate through which a horse could have passed; a man could have sat down in one of the eyes.” Hokusai followed up this triumph by painting, on a colossal scale, a horse, the fat god Hotei, and the seven gods of good luck. At the same time, to show the range of his powers, he made microscopic drawings on grains of wheat or rice, and sketched upside down, with an egg, a bottle, or a wine measure. These tricks gained him such a reputation that he was commanded to draw before the Shogun, an honour almost without precedent for a painter of the artisan class. Here he created a sensation by painting the feet of a cock and letting it walk about in the wet colour spread on his paper, till the result was a blue river covered with the floating leaves of the red maple.

In 1807 his connection and squabbles with Bakin, the famous novelist, began. They first collaborated on a book, The Hundred and Eight Heroes, which Bakin translated from the Chinese, while Hokusai furnished the pictures. The connection lasted about four years, and was dissolved by an unusually violent quarrel. The pair seem indeed to have been ill-matched. Bakin, serious, distant, absorbed in his literary studies, possibly a bit of a pedant, was no companion for the quick capricious artist. Hokusai’s first acquaintance with the actor Baiko was equally characteristic. Baiko, who was especially famous for his manner of playing ghosts, one day sent to ask Hokusai to draw him a new kind of phantom. No reply came, so Baiko called in person. He found the painter in a room so filthy that he had to spread out a rug he had prudently brought with him before he could sit down. To his attempts at polite conversation, and his remarks about the weather, Hokusai made no answer, but remained seated without even turning his head, till at last Baiko had to retire angry and unsuccessful. In a few days he returned with humble apologies, was well received, and from that time forward the two were friends.

In 1817 Hokusai went to Nagoya for six months, staying in the house of a pupil. Here he repeated the tour-de-force that had gained him so great a reputation at Yedo, by painting a colossal figure, in the presence of a crowd of spectators, on a sheet of paper so large that the design could only be shown by hoisting it on to a scaffolding with ropes. More important, however, than this advertisement of his dexterity, was the publication of the first volume of the Mangwa, which, according to the latest authority, appeared at this time. The word has been variously translated by such expressions as “various sketches,” “spontaneous sketches,” “rough sketches,” “casual sketches,” and so on. The exact meaning is ambiguous even for cultured Japanese, so that it is unnecessary to discuss the matter further here. This volume was the first of the famous series of fifteen which contains so much of the artist’s best work.

In 1818 he continued his travels, visiting Osaka and Kioto before returning to Yedo. It would seem that in the ancient capital of the Mikado, Hokusai met with but moderate success. The place was the headquarters of the classical schools of painting, and its refined connoisseurs would recognise but little merit even in the best productions of the popular art. Ten years later, when nearly seventy years old, he was attacked by paralysis, but cured himself with a Chinese recipe that he found in an old book. This recipe for boiling lemons in saké (rice-spirit) is still extant, with drawings by Hokusai of the lemon, the manner of cutting it, and the earthen pipkin in which the mixture is to be cooked. Whatever the merits of the medicine, the old artist was thoroughly cured, for it was about this time that he produced the three sets of large colour-prints which are, perhaps, his most important works, the Waterfalls, the Bridges, and the Thirty-six Views of Fuji. It is possibly owing to the misfortunes of the following years that these series seem to be incomplete. Certainly Hokusai had good reasons for not undertaking any commissions that did not bring in ready money, for in the winter of 1834 he had to fly from Yedo and live in hiding at Uraga under an assumed name. The reason of this flight is uncertain, except that it was caused by the misdoings of a grandson. A letter to his publishers explains the measures taken for the reformation of the scapegrace; the purchase of a fish shop, and the provision of a wife “who will arrive in a few days” — at Hokusai’s expense.

When writing from Uraga he would not give his address, though he suffered great privations ; and when important business recalled him to Yedo, he visited the capital secretly. It was not till 1836 that he was free to return safely; but the return came at an unpropitious time. The country was devastated by a terrible famine, and Hokusai found that the ordinary demand for art had ceased. To live he was compelled to work day and night, turning out quantities of drawings whose chief recommendation to the public was their cheapness. At last he was reduced to such straits that he had to eke out a precarious existence on handfuls of rice, gained by exhibitions of his manual dexterity. In the following year his patience was again severely tried by a fire that burned his house and all his drawings. Only his brushes were saved; and the poor old man had to keep more constantly than ever to his work, both as a consolation in his troubles and as means of avoiding starvation. Year after year he went on designing with undiminished power and activity; but though he never emerged from the state of chronic poverty that had surrounded him all his life, he never seems to have been again threatened by positive want. Certainly in old age he lost nothing of his skill and little of his cheerfulness, if we may judge from a letter written to a friend during his fatal illness in 1849.

“King Yemma (the Japanese Pluto) being very old is retiring from business, so he has built a pretty country house, and asks me to go and paint a kakemono for him. I am thus obliged to leave, and, when I leave, shall carry my drawings with me. I am going to take a room at the corner of Hell St., and shall be happy to see you whenever you pass that way. HOKUSAI.”

On his deathbed he murmured, “If Heaven could only grant me ten more years!” Then a moment after, when he realised that the end had come, “If Heaven had only granted me five more years I could have become a real painter.” With this rather unreasonable regret on his lips Hokusai died on 10th May 1849, in his ninetieth year.