Biography of Henry Morton, President of the Stevens Intitute of Technology circa 1894

Dr. Henry Morton was born in the city of New York, at the residence of his maternal grandfather, on Varick street, facing what was then St. John’s Park, now occupied by the immense freight depot of the Hudson River railroad.

At the age of seventeen young Morton entered the sophomore class of the University of Pennsylvania, graduating in 1857, and on leaving college, entered the law office of Mr. Geo. M. Wharton as a student. During his last year at college and his first in Mr. Wharton’s office he prepared and drew on stone the now rare volume containing translations of the hieroglyphic and other inscriptions on the famous Rosetta Stone, with numerous colored illustrations and illuminations, which received high commendation from Baron von Humboldt and other scholars. At the end of two years, however, seeing an opportunity of engaging in scientific work, which had been a favorite subject with him since his boyhood, he gave up the study of law and accepted the position of science instructor in a large endowed school — the Episcopal Academy — at Philadelphia. Here he worked and lectured for several years, until in 1864 he was offered the position of resident secretary of the Franklin Institute of Pennsylvania.

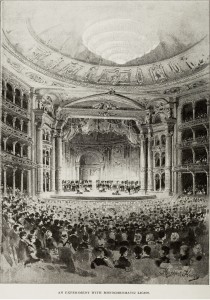

In order to augment the usefulness and pecuniary resources of this institution it was decided by the board of managers that a course of scientific lectures should be delivered in some large hall. One of the managers was even so bold as to suggest the Opera House or Academy of Music, one of the largest auditoriums then in the country, seating over 3500 persons. Others considered this too venture-some, but it was finally agreed to leave this to Mr. Morton’s decision. Deputed to communicate with Mr. Morton on this subject, the present writer well remembers the characteristic courage and enthusiasm with which he at once seized on the idea of making the so far unparalleled experiment of devising and executing illustrations on a sufficient scale to render them impressive on so large a stage and to so vast an audience.

All who came in contact with him were inspired with his confidence (myself among the number), and preparations were commenced at once. Some notice of these got abroad and long before the date assigned every seat in the house was sold, and the house having been engaged for a repetition on a succeeding night, every seat for this second performance was also sold before the night of the first delivery. There are occasions, even in the life of a scientific professor, which call for no small amount of moral courage, and the evening on which, for the first time, Mr. Morton walked forward upon a public stage, in the face of an audience which crowded every seat and every foot of standing room, with the consciousness that he was committed to the absolute necessity of a success by the arrangements for the repetition was one of them. I was with him at the time, having undertaken the office of manager, to direct the work of his assistants on the stage, and I have not forgotten what were my own feelings. But when the curtain rose, he stepped forward with easy grace amid the enthusiastic applause which greeted his appearance, and began his lecture as calmly and collectedly as if he had done the same thing fifty times before. He told me afterward that he was so anxious about the success of his experiments that he had no room in his mind for personal embarrassment or the nervous agitation often caused by facing a great audience. I need hardly say that the lecture was a success. The clearness of the explanations and the novelty and beauty of the experiments held the audience in close attention for nearly two hours, and when Mr. Morton made his exit amid applause even heartier than that which had welcomed him, he carried with him a reputation as a scientific lecturer second to none.

During the following years similar lectures on related subjects were given by Mr. Morton in the same place. Some of their titles were the following:

“Reflection,” “Refraction,” “Sunlight,” “Moonlight,” “Eclipses,” and “Fluorescence.” In these lectures Mr. Morton used not only numberless devices for the production of striking illustrations of scientific phenomena, but also brought into play the appliances of the stage, such as shifting scenery to aid in color effects, stage traps to bring apparatus into position as wanted or to aid in the development of experiments. I will here describe a few of these combinations from various lectures.

It was in one case desired to show the effect of light having only one color or wave length, in the illumination of colored objects generally.

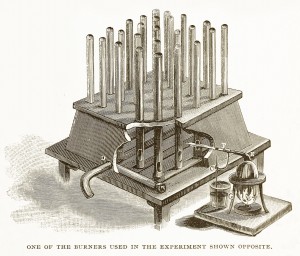

When the time came for this experiment the drop curtain which had descended behind the lecturer for a few minutes was raised again revealing a brilliant “palace scene,” illuminated by numerous lights judiciously placed. There then marched in a great number of masked figures in costumes representing the colors of the spectrum and bearing banners with brilliant devices. These, taking positions, formed a tableau blazing with variegated colors. Then in a moment all the lights were turned off, while at the same instant a number of monochromatic burners replaced the former illumination with floods of yellow light which lit up every part of the stage and also of the auditorium, but with the absolute extinction of every shade of color. The figures on the stage as well as the audience were in an instant reduced to grizzly phantoms, clad in gray and black. The illustration […] shows the interior of the opera house during this experiment. Toward the middle of the stage are seen the four monochromatic burners which were devised by Mr. Morton, and which were constructed in the manner indicated by the annexed cut, in which are represented twenty-five Bunsen burners, receiving their gas supply from a gridiron of pipes and their air supply from the box which encloses their lower ends, and has but a single opening, in front of which is set a steam atomizer, by which a spray of salt solution can be, at will, driven into the box. The burners, when lit, give only a mass of blue, non-luminous flame, but as soon as the spray of salt water is fed into them with their air supply, this flame becomes brilliantly luminous, but with light truly monochromatic, or yielding only the yellow rays due to sodium.

In another lecture the following effects were produced on a screen which filled the whole width of the stage in place of the drop curtain: First, the entire space of the stage seemed to be transformed into a vast tunnel, from the further end of which a locomotive rapidly advanced until it towered up of gigantic size and seemed about to plunge into the orchestra. At this moment a whistle sounded, and at once tunnel, locomotive, and all melted into an ocean grotto with a sea nymph, who presently retired into its distant depths.

These phantasmagoria experiments were arranged by having a large magic lantern on an elevated structure at the extreme rear of the stage, which was 60 feet deep, and, with this, throwing large pictures, as of the tunnel, grotto, etc., so as to cover the 40-foot screen at the front of the stage. On a carriage running at right angles to the screen — that is, back and forth on the stage — were mounted two magic lanterns, with the gas bags, etc., required for their calcium lights. Each of these lanterns was provided with a mechanism by which the adjustment of the lens, securing a sharp image at various distances, caused the opening or closing of a diaphragm which controlled the amount of light passing from the lens to the screen. By this means, uniformity of illumination was secured during the change in size of the image.Thus, in the tunnel experiment, the view of the interior of the tunnel was thrown on the screen by the large fixed lantern. Then, the lanterns on the carriage being close to the screen, a small image of a locomotive, seen from the front, was also thrown on the screen so as to occupy the far-off end of the tunnel. The carriage was then slowly rolled back on the stage, an assistant keeping the focus right by means of the rack and pinion on the lens as the image grew larger in consequence of the increasing distance of the lantern from the screen. This adjustment of the focus automatically opened the diaphragm, so that, as the image grew larger, more light passed out to illuminate it.

When the two lanterns on the carriage had reached the most distant part of their movement, the image of the locomotive was so expanded as to occupy the entire screen, and at this moment the “dissolving stopcock” was turned so as to change the light from one lantern to the other, and thus slowly change the locomotive into a nymph. At the same time that this was being done, a picture of the interior of a grotto was substituted for the tunnel in the large lantern, unnoticed by anyone in the confused effect produced by the melting of the other images, one into the other, and thus, when the sea nymph was fully defined, she was seen to be seated, not in a tunnel, but in a grotto festooned with sea weeds and strewn with shells.

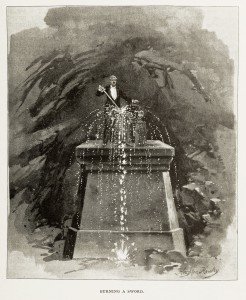

On another occasion, in order to illustrate certain luminous effects of intense heat, a large pedestal was built upon one of the regular “lifts” used in connection with stage “traps”‘ in its lowered position, so that the top of the pedestal was on a level with the stage floor. At the proper time the lecturer placed himself and apparatus on this pedestal, and was then raised to a considerable height above the stage, at which elevation he burned, in the oxyhydrogen blowpipe, a sword from point to hilt. The effect of this experiment is well shown in the illustration […].These are but a few typical examples out of dozens of the same general character, which limits of space forbid my even mentioning, but 1 can truly say that, though I have witnessed many of the most famous scientific lectures delivered during the last twenty-five years in this country and abroad, I have never seen anything to compare with these delivered by Mr. Morton. In this connection I would relate an amusing incident of which I was a witness. When Prof. John Tyndall, F.R.S., etc. , made his famous lecturing tour in the United States in 1872, he met President Morton soon after his arrival, and was hospitably entertained and offered every assistance available. Among other things, President Morton presented him with one of his eclipse slides by means of which all the phenomena of a total solar eclipse are projected on a screen, and a large drawing in certain fluorescent substances, discovered by President Morton shortly before, and exhibiting this action in a conspicuous manner.

Now it happened that Prof. Tyndall never thought of trying this fluorescent design until, when in the midst of one of his lectures at Philadelphia, he came to speak of this property of light. Some accident of association then brought this design to his mind, and with the off-hand informality which was one of the charms of his address, he said to his assistant : “By the way, Mr. Cotterill, we have somewhere a fluorescent design which Dr. Morton gave us, — some new substance which he has discovered. If it is at hand, hold it up in the beam of violet light and let us see how it looks.”

Mr. Cotterill promptly found the design and held it up, when it blazed out with intense green and blue radiance so as to startle even the lecturer, who exclaimed: “Good Heavens! I never saw anything like that in my life.” The effect of this on the audience, most of whom knew Dr. Morton personally and had attended his lecture on “Fluorescence” shortly before, may be well imagined.

In 1867 Dr. Morton was made editor of The Journal of the Franklin Institute.

In 1868 he accepted the Chair of Chemistry and Physics in the University of Pennsylvania, and in 1869 he organized and conducted an expedition to make photographs of the total eclipse which occurred on August 7 of that year. This work was most successful, and its results constituted a valuable contribution to physical astronomy. In this connection Dr. Morton was fortunate enough to discover and demonstrate, by experiment, the true cause of the bright line on the solar disk along the moon’s edge, seen in photographs of eclipses, which had been an unsolved problem up to that time. In the same year Dr. Morton received the title of Doctor of Philosophy from Dickerson College, Carlisle, Pa., which was again conferred by Princeton College, N. J., in the succeeding year.

In 1870 Dr. Morton accepted the position of President of Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N. J., which had just been founded by a bequest of the late Edwin A. Stevens, Esq. At the time when President Morton took charge of the institute he formulated such a working plan for the future school as the needs and knowledge of the hour suggested. This plan was purposely left flexible as to its details, and many modifications have been made, but these have always been in the line of evolution and development and not in that of abandonment and departure.

To write in any detail as to this part of President Morton’s life would be to give the history of the Stevens Institute, and I will therefore in this connection only advert briefly to the generous gifts by which he has from time to time supplied what was needed to meet the growing demands of the Institute. In 1880 he presented to the trustees a new workshop which he had fitted up with steam engines and tools at a cost of over $10,000 ; in 1882 he supplied the sum of $2500 for electrical apparatus, and also contributed the salary of the Chair of Applied Electricity for a number of years ; in 1888 he presented to the trustees the sum of $10,000 toward the endowment of a Chair of Engineering Practice; and in 1892 he presented to the trustees the further sum of $20,000 toward the further endowment of the same chair.

In 1873 President Morton was elected a member of the National Academy, and in 1878 he was appointed a member of the United States Light-house Board to fill the vacancy occasioned by the death of Professor Joseph Henry.

It would be quite impossible within the limits of this article even to give the titles of President Morton’s contributions to scientific literature. His researches have been chiefly on the subjects of chemistry and of light, though many other fields have been locally cultivated by him. Soon after his settlement at Hoboken, he was called upon to advise and assist, as a scientific expert, in an important patent litigation, and the efficiency of his investigation in this case soon led to his being called upon in others, also involving difficult scientific problems, and thus he soon gained and has since held the position of leading scientific expert in New York and its vicinity, and the revenue derived from this class of professional work has enabled him to contribute to the growing needs of the Stevens Institute of Technology, not only by the large donations already noted, but by many others involving less amounts, but large in the aggregate, and of enhanced practical value from their timely application.

One of the most prominent stenographers employed in the New York courts once said to the present writer, “We have less trouble in taking down President Morton’s testimony than with that of any other witness. He always says what he means and sees his way ahead so far that if there are ambiguities, or forms of expression likely to lead to confusion in the questions put to him by the lawyers on either side, he always straightens them out in the first instance, and so avoids the confusion which often arises from a lack of clear statement. He loses no time in making his answers and thus, without hurry, gets through a vast amount of work in a day.”

The taste for drawing which led Mr. Morton in his college days to illuminate the Rosetta Stone Report continued to prove useful to him in his subsequent work. While editor of the Franklin Institute Journal he frequently drew on stone illustrations required for that publication, and constantly prepared pictures or diagrams for the illustration of his lectures.

In later life he has been able to gratify his artistic taste by collecting a number of paintings by our best American artists of the non-impressionist school, such as Hertzog, McCord, Ferguson, Bricher, Craig, Turner, Hawley, and Davis, which delight all those who take pleasure in what is intrinsically beautiful. In The Century Magazine for December, 1890, and for May, 1893, will be found examples of a poetic vein which casual acquaintances would not have suspected but which has often been a source of pleasure to his intimate friends.