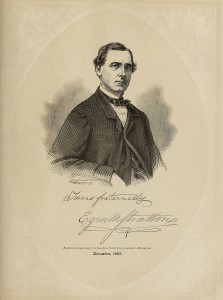

Ezra M Stratton Autobiography Circa 1863

It is sufficiently difficult to write the biography of any living subject; but when one undertakes to give his own history, the difficulties increase manifold, as it imposes a heavy tax on his modesty, and may seriously expose him to criticism. In this instance two reasons induce the writer to act as he does the first is that, during his editorial career, his readers have frequently requested him to give them his portrait, that they might see how he looked; the second, that he is under obligations to give at least one portrait of some coach-maker in each volume, and no other being available at this time, seems to offer an apology for its appearance. The biography accompanying it will be purposely brief.

The writer is the oldest of five children, and came into this troublesome world on the 11th day of May, 1809, at a place known in the locality as Benjamin’s Hill, Parish of Green’s Farms, Fairfield County, Connecticut. Like many other literary men, he was born in a cottage of humble pretensions; but this cottage was situated on one of the loveliest sites bordering on Long Island Sound. As if by inspiration, Dwight, in his “Greenfield Hill,” has truthfully sung the beauties of the prospect from this spot:

” Here, crowned with pines

And skirting groves, with creeks and havens fair

Embellished, fed with many a beauteous stream,

Prince of the waves, and Ocean’s favorite child,

Far westward fading in confusion blue,

And eastward stretched beyond the human ken,

And mingled with the sky, there Longa’s Sound

Glorious expands. All hail! Of waters first

In beauties of all kinds; in prospects rich

Of bays, and arms, and groves, and little streams,

Inchanting capes and isles, and rivers broad,

That yield eternal tribute to thy wave!

In use supreme: fish of all kinds, all tastes,

Scaly or shell’d, with floating nations fill

Thy spacious realms; while, o’er thy lucid waves,

Unceasing commerce wings her countless sails.

***** Round yon isles,

Where every Triton, every Nereid, borne

From eastern climes, would find perpetual home.

Were Grecian fables true, what charms intrance

The fascinated eye! where, half withdrawn

Beyond yon vivid slope, like blushing maids,

They leave the raptur’d gaze. And 0, how fair

Bright Longa spreads her terminating shore,

Commixed with whit’ning cliffs, with groves obscure,

Farms shrunk to garden-beds, and forests fallen

To little orchards, slow-ascending hills,

And dusky vales, and plains! These the pleased eye

Eelieve, engage, delight; with one unchang’d,

Unbounded ocean, wearied, and displeased.”

Descended from Puritan stock of the fourth generation, he has the satisfaction of knowing that, on the maternal side, his grandfather was the celebrated Capt. Solomon Morehouse, of the Revolutionary Army, and a personal friend of Gen. George Washington, for whose character he entertained a respect bordering on fanaticism.

On the paternal side very little can be said, except it be that his grandfather was an honest weaver, anterior to the introduction of machinery into this country for the fabrication of cloths, and that the good cider his cellar contained always brought him plenty of friends. The father of the writer was a farmer, who never rose to any higher public office than that of Lieutenant in the Connecticut Militia; and his only exploit with his sword, as he humorously boasted, was to vanquish a rat who defiantly faced him one evening on the cellar wall. His personal character was such as to challenge the respect of all who knew him, and is well expressed in the reply made by that late eminent lawyer of Westport, Samuel B. Sherwood, Esq., to a skeptic, who said, ” I do not believe there is a truly honest man on earth.” “Yes, there is,” said the squire. “Who is it?” “Eliphalet Stratton,” was the quick reply.

The author of Caleb Snug (see page 22, Vol. III.) has already, under an assumed name, given a very good sketch of the life of the Editor, and, among other things, he says that his neck was so weak in his babyhood that, to prevent its breaking, the constant care of a nurse was demanded. “About these days,” as the almanacs have it, a circumstance occurred which came near prematurely ending the drama, as far as he was concerned. While sleeping at night another of the rats, with which the cottage appears to have been infested, opened a vein on the bridge of his nose, which at the time proved a serious affair, and the marks of whose teeth can be seen to this day. The only other occurrence to be noted, in this cottage, is the fact that the writer having, when three years of age, climbed up to the second floor, on a flight of stairs devoid of rails, a misstep precipitated him, head foremost, some ten feet, which, as he remembers, caused an “awful squalling.” It may thus be seen that, like Hercules, the writer had his trials before he got into pantaloons.

When about five years of age the Avriter was sent to the District School, for three months during the Winter and four in the Summer season, until ten years of age; after that, until sixteen, only for short periods during the Winter — his time being required on the farm. Although the writer was very industrious in committing his lessons to memory, and very successful in carrying off prizes, “the rewards of merit,” yet he remembers that on one occasion he was induced to play truant with some other boys for one-half day. This act, also, was rewarded with two lickings — one, when he went home at night, from his parents, and another the next day, at school, from the master — both of which served to dampen his ambition in that line of business. While very young, he was given to making sketches of any interesting object which came in his way, and these were accompanied by poetical descriptions, which attracted attention from his acquaintances, and received their commendations at the time. His education — if he has any — has mainly been the result of private study, and to accomplish which he may briefly state, without boasting, he has devoted at least six hours of his life daily, for over thirty-five years.

The mechanical life of the writer dates from April, 1824, when he was apprenticed to Charles Townsend, of the firm of Piatt & Townsend, of Saugatuck (now Westport), Connecticut. There he spent over five years of his life; with how much comfort, the reader may gather from “The Autobiography of Caleb Snug,” already published in earlier numbers of this Magazine. Suffice it here to say, that nearness to his parental domicile was a fortunate circumstance for him, as it relieved him from starvation on more than one occasion. Boys who are apprenticed to trades now know nothing of the hardships endured by the former generation of apprentices. May they never experience them!

Having stayed his time out faithfully, the writer soon after removed to New York City, where, after two or three years’ labor as a journeyman, he started business on his own account, in 1836, with such success that he has paid his way, and put a little in his pocket for ” a rainy day.” During these thirty years of city life his pen has not been idle, as numerous publications testify; although up to 1858, when this Magazine commenced, he had no pecuniary interest nor active editorial labor on any. It is true he once allowed his name to appear as an assistant Editor, to give a character to a Western publication, but which he regrets having done to this day — not because he lost pecuniarily by the operation, but that, like Tray in the fable, it turned out that he got into bad company — at least he found out that the stranger to whom he lent his character proved afterwards to be “no better than he should be.” When this became known he immediately “cut loose,” and started this Magazine; with what success, the public must know already. The acquaintances he has made with some of the best minds in the trade has been very gratifying, and he is happy to number individuals among his regular correspondents who have done much to adorn the literature of their country. It is true, his editorial life has not been all sunshine; some who ought to have stood by him have proved false friends; but, in the main, it has been the happiest portion of his days.