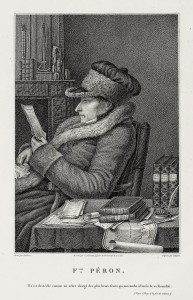

Francois Peron Biography

DIED: December 14, 1810

[republished from The naturalist’s library (1833) by Sir William Jardine]

EARLY YEARS AND EDUCATION

FRANCOIS PERON was born at Cerilly, in August 1775. From his earliest years his intelligence exhibited itself by his extreme curiosity, and an insatiable desire for information. Scarcely had he learnt to spell, when his passion for reading became so strong, that, to gratify it, he had recourse to all those little arts to which children usually resort to procure their play.

The death of his father having deprived him of all resources, his relatives wished to engage him in some lucrative trade. Almost in despair at the thoughts of being torn from his favourite delights, he prevailed on his mother to send him to the College of Cerilly, where the Principal, delighted with the tastes of his scholar, became much attached to him, and spared no pains on his improvement.

His elementary studies being finished, he advised him to become an ecclesiastic and the curate of the town consented to take him under his roof, and superintend his professional pursuits.

MILITARY SERVICE

Up to this period, Peron, absorbed in his studies,was quite ignorant of the extraordinary events which were then agitating the world. He heard of them with astonishment; and, seduced by those principles of false liberty which led to the Revolution, inflamed by what is misnamed patriotism, and seduced by the examples of ancient history, lie

longed to embrace the profession of arms. He then quitted his home, betook himself to Moulins, and joined the battalion of L’Allier, towards the close of the eventful year 1792. He was soon sent to the army of the Rhine, and found himself at the Siege of Landeau, where the garrison maintained a most obstinate defence. After the siege was

raised, he rejoined the army in the field, fought in the battle of Wissembourg against the Prussians, and was again present when the French experienced a defeat at Kaiserslautern. On this occasion Peron was wounded and taken prisoner; he was soon conducted first to Wesel, and then to the Citadel of Magdebourg. It was many years after the occurrence of these events, when, on the bosom of the wide Atlantic, he entered in his private journal the following reflection: “Alas! how many excesses and villanies have soiled the trophies of our soldiers! how many a deep sigh have they wrung from my heart! I could not, indeed, restrain them; but I never joined in them: though I was young and enthusiastic, yet the rights of misfortune were always sacred in my eyes.”

During his captivity he gave himself up to study, to which even when on service he was much addicted; and now that he had no other employment, he devoted himself, without distraction, to the reading of history, and the careful perusal of voyages and travels. Being liberated from prison, in exchange, in 1794, he was discharged from the army on account of the loss of an eye, and returned home in 1795, at the age of twenty.

LATER EDUCATION

After remaining several months in the bosom of his family, wishing for some active and honourable employment, he solicited the Minister of the Interior that he might become an eleve of the Medical School of Paris, where, for three years, he not only studied Physic, but also devoted himself to Zoology and Comparative Anatomy, and then took his degree His previous study of Mathematics, of Languages, of Philosophy, and, most of all, his own reflections, had given him such a methodical turn, that he was enabled to arrange and classify his knowledge with wonderful rapidity, in every department of science, and to an extent that astonished his associates.

ROMANTIC LIFE

But, whilst ambitious of distinction, and enamoured with study, a still stronger passion now took possession of his heart; he loved with all his constitutional enthusiasm; but his suit being rejected, on account of his poverty, he was almost driven to despair. His distress was extreme, and he took a disgust even to his country, in which his cruel dis-

appointment was often forced on his notice, and where he no longer expected either comfort or peace.

EXPEDITIONS

Not being eligible for the army, he looked round for some other adventurous career, and the Government Expedition to the Southern Hemisphere, consisting of two frigates, Le Geographe and Le Naturalist, being on the eve of departure, he solicited an engagement in the service; but the complement of Savants being filled up, his offer was rejected.

Under these circumstances, he applied to M. de Jussieu, one of the Commissioners for the appointment of Naturalists, imploring his good offices, and at the same time explaining his views with an enthusiasm which manifested he was capable of executing what he so boldly planned. Jussieu listened with astonishment, and advised him to present a written explanation of his plan. He then recounted to his colleagues his conversation with M. Peron; and, in concert with Lacepede, determined not to repel a young man in whom was conjoined such extraordinary energy, with an extent of information much above his years.

Some days after, M. Peron read to the Institute a Memoir on the importance of adding to the other Savants of the Expedition a person who was at once a Physician and a Naturalist, and who would especially undertake to make

researches on Anthropology, or the natural history of man. Every one was delighted with the suggestion, and the Minister conferred on Peron the appointment of Zoologist to the Expedition. The short time that was now at his disposal he employed in obtaining from Messrs Lacepede, Cuvier, and others, such hints as would be useful in his researches. He determined to devote his energies principally to Zoology, as that portion of Natural History which presented the widest and most inviting field. He procured the necessary books and instruments ; bid adieu to his relations at Cerilly, and, smothering that affection which had so overwhelmingly affected him, he proceeded to Havre.

The Expedition sailed on the J9th October 1800; he, with most of the Savants, being on board Le Geographe.

Though several campaigns had familiarized M. Peron with privation, yet, on board of ship, he found himself more put about than he anticipated. Having arrived after all the others were accommodated, there was but a pitiful corner left for him; however, in the midst of agitation and bustle, he retained all his composure and self-possession, and did not lose a moment. The very day he went on board he commenced his meteorological observations, which he constantly repeated every six hours, and which were never interrupted during the whole course of the voyage.

Shortly after sailing, he made some important experiments regarding the temperature of the water of the ocean, which demonstrated it was colder in proportion as the depth increased. On reaching the Equator, the whole crew were greatly astonished by an appearance which presented itself. One night, when the heavens were very dark and cloudy, a bright band, as of phosphorus, covered the water at the horizon; presently the ocean seemed in a flame, and sparks of fire appeared to rise from its surface. Our voyagers had often witnessed the phosphorescence of the sea, but they had not seen the aurora borealis, for which they took it; but, on advancing, they discovered that this extraordinary light was produced by a countless multitude of small animals which appeared like sparks of fire. Many of them were brought on board, and M. Peron found, on examination, that they successively assumed all the colours of the rainbow, at first

shining with great brilliancy, till their usual irritability being enfeebled, their colour faded, and entirely disappeared.

The impression which this phenomenon made on Peron, and the peculiarities presented by the organization of these zoophites, determined him to investigate this class of animals; and, during the whole of his voyage, he* and his friend Lesueur were ever watching at the ship’s side, that they might collect all they could procure. No new object in

Natural History can be accurately comprehended without the aid of figures, and hence the great importance of designing, to a Naturalist. Peron was no great artist himself, but his friend Lesueur, who was, moreover, an excellent observer, drew, under his direction, those gelatinous animals whose forms and colours changed every moment after they were taken from the water. The two friends laboured in concert; the one painted, the other described; in their work they had but one soul, and neither wished to exalt himself at the expense of the other.

After a voyage of five months they reached the Isle of France. Here they completed their stores for the Antarctic Seas; and some of the Naturalists, not receiving the necessaries they expected, and discontented with the treatment they experienced, remained in the colony, whilst Peron considered himself bound by his engagement. Our limits do

not permit us to follow him through all the details of his adventures, but we shall stop a moment at those spots which formed the principal scenes of his labours.

Sailing from the Isle of France, they shaped their course to the Western Shores of New Holland, and anchored in a bay which, from the vessel which first rode in it, they named Geography Bay. They then skirted along the Western Coast, surveying many harbours, and anchored for refreshment at the Island of Timor.

It is chiefly to Peron’s stay in this spot that we are indebted for his labours on the Mollusca and Zoophites. The sea is shallow, and the excessive heat seems to multiply prodigiously these singular animals, and to adorn them with the brightest colouring. Peron spent nearly the whole day on the shore, plunging into the water in the midst of the surf, always at the danger of his health, and sometimes of his life. With the shades of evening he returned from his work, loaded with numerous specimens, which he reviewed, and of which his friend sketched the most remarkable objects. Neither the misfortunes which had befallen the other Naturalists, nor the dangers with which he himself was threatened, had any power to relax Peron’s zeal. Nor did his industry, in collecting the innumerable productions of nature, hinder him from finding time for observations of a different kind.

He spent many days in penetrating into the interior of the island, and in examining the aborigines. Though he did not understand their language, he possessed such a ready power in comprehending their gestures, and the inarticulate language of nature, that, to a great extent, he understood them; and he had the same success with the savages of New Holland and Van Dieman’s Land.

Struck with the fact that, during their stay at Timor, his companions were almost all sick, whilst the natives were not suffering, he set himself to investigate the cause of the difference, and discovered it in the use which the inhabitants make of Betel, or water-pepper.

On leaving Timor, they sailed direct for the South Cape of Van Dieman’s Land. After having surveyed its Eastern portion, they entered the Bass Straits, and then followed the South Coast of New Holland. Here they suffered extremely; and when they reached Port Jackson, their condition, from privation and disease, was such, that only four of the crew could perform duty; so that, had they been detained a few days longer at sea, they must all have perished.

On reaching this friendly port, Peron again found himself in the midst of civilized society, and received many marks of kindness and consideration. But instead of resting from his fatigues, he only enlarged the limits of his labours. He prosecuted his researches into the physical history of man, by studying the civil and political constitution of this most wonderful colony, whose laws, at once sage and severe, have converted highwaymen and robbers into industrious labourers; and where depraved women, without character, have abandoned their vicious courses, and become the respected mothers of thriving families.

After their departure from Port Jackson, whence Le Naturalist was dispatched to France, another voyage, no less hazardous than the former, was undertaken. Le Geographe proceeded to examine the islands at the western part of Bass Straits, again to explore the coast of New Holland, skirting along it as far as the Gulf of Carpentare. The

dangers increased on every hand on these unsurveyed coasts, and were most severely experienced by the Naturalists, who lost no opportunity of penetrating into the interior.

Peron, especially, displayed remarkable courage and activity. He went in quest of the rude savages, without being

alarmed at their perfidy or ferocity ; he also collected a great number of animals of all kinds; he seized every opportunity of examining into their habits, to discover any that might be useful to mariners on the desert land, or would be capable of domestication, or might be naturalized in Europe, or, finally, might become objects of commerce, for their fur, oil, or other products. Of the five Zoologists who had been appointed by government, two having remained at the Isle of France, and two having died at the commencement of the second voyage, Peron alone remained for the performance of the duty, and he did it all.

Engrossed in the great designs in which he was embarked, he regarded not the privations to which he was subjected. Shortly after their departure from Timor, the captain having refused the spirits which were necessary for the preservation of the Mollusca that were collected, he appropriated the whole of his personal allowance to this purpose; and, what was still more remarkable, his enthusiasm spread to many of his companions, who followed his example, and made the same sacrifice.

It was, especially, in the midst of dangers that Peron exhibited the energy of his character, his powers being redoubled when he encountered difficulties. During storms he used to work as a common sailor, and all the while would be observing as composedly as if he were ashore. No event diverted his attention from whatever promised a useful result, and he was always quick in improving circumstances.

Having gone ashore on King’s Island with M. Lesueur, and several other of his companions, a sudden gale drove the ship to sea, and they saw nothing of her for fifteen days. Peron did not for an instant lose his equanimity; he patiently prosecuted his researches without foreboding the evils which might betide. During his stay on this island, whose most magnificent vegetation presents nothing for the nourishment of man, he, without shelter, and in despite of the violence of the tempests, collected more than 180 species of Mollusca and Zoophites; he, moreover, studied the history of those gigantic seals, the Proboscidea, which assemble in thousands on the coasts, and whose history forms a striking feature of our volume; and he examined the habits and mode of life of a small colony of eleven miserable fishers, who, separated from all the world, prepare in this place the oil and skins of the Seals, which the English traders come at distant intervals to procure. These poor people live in huts, and feed upon the Emu or Cassowary and Kangaroos, caught by dogs trained for the purpose, and upon the Wombats they have domesticated. They readily shared their meagre fare with the strangers, and treated them with a hospitality which is often more strikingly exhibited among a simple and feeble race, than in the midst of civilized society.

During their last sojourn at Timor, Peron completed the observations he had previously commenced there. He had frequent intercourse with the natives, and now more mature^ studied their manners, government, and character, because he better understood their language, which is a dialect of the Malay. With no other associate than his friend Lesueur, he did not fear to chase the numerous crocodiles which, to the inhabitants, are objects alike of terror and veneration. Without other help they killed one of these animals, and prepared the skeleton, which now adorns the gallery of the Paris Museum.

Being prevented by contrary winds from touching at New Guinea, they returned to the Isle of France, where they remained five months. There Feron, after examining his collections, devoted himself to the study of its fish and Mollusca; and, notwithstanding the exertions of preceding Naturalists, he collected many new species. After this, they remained a month at the Cape, where he improved the time by making the first accurate examination of the singular conformation of a tribe of the Hottentots, known by the name of Bushmen, many of whom happened at the time to be at the Cape.

RETURN TO PARIS AND CERILLY

Finally, after an absence of three years and a half, he landed at L’Orient in April 1804, and immediately proceeded to Paris. He was there engaged for several months in arranging the specimens, and preparing the catalogue, after which they were all deposited in the Museum. Peron then hastened to Cerilly, to visit his mother and sisters.

The exhausted state of his health, arising from his long continued fatigue, and still more from the nascent germ of that disease, which was even now working in his frame, made repose absolutely necessary; and, happy in finding himself in the bosom of his family, after having done good service, he thought little on the recompence of his labours.

DEFENDING THE RESULTS OF THE EXPEDITIONS

He soon, however, heard that some were endeavouring to persuade the government that the grand objects of the expedition had failed; and this immediately brought him to Paris to refute the calumnious imputation. He visited the Minister of Marine, and, with him, found M. de Fleurieu, and several other savants.

Before them all, in a modest and respectful tone, but at the same time with confident freedom, he demonstrated what his companions had done for geography, mineralogy, and botany; he enumerated the objects which had been procured, the drawings which had been executed, and the observations and descriptions which had been amassed, saying but little of the dangers which had been endured, and the sacrifices which had been made in obtaining the collection. Questions were put to him, which he answered promptly and satisfactorily; and the impression made upon the minister was such, that, after requesting him to visit him at all times, he engaged his services, to prepare for publication the nautical portion of the voyage, and promised to speak to the Minister of the Interior concerning the historical part.

Accordingly, he had the same success with this latter functionary, who entertained him in the most flattering manner, and appointed him, along with his friend Lesueur, to publish the account of the whole voyage, including a description of those objects which were new in Natural History. Thus was Peron, all at once, placed in the ranks of celebrated men; he was courted and surrounded by admirers, and took pleasure in relating what he had witnessed in his voyages; and the interest with which he was listened to often induced him to enter into minute details.

THE SPECIMENS – COLLECTIONS

In the meanwhile, the collection, now arranged in the Museum, was to be examined, and a commission named by the Institute was appointed to report to Government. This commission was composed of Messrs Laplace, Bougainville, Fleurieu, Lacepede, and Cuvier; and their report, drawn up by Baron Cuvier, bore that the collection contained more than 100,000 specimens of animals, amongst which were many new genera; that the number of new species was more than 2500, and that Peron and Lesueur alone, had made us acquainted with more animals than the whole of the travelling Naturalists of modern times ; and, finally, that the descriptions of Peron, prepared upon a uniform plan, embracing all the details of the external organization, establishing their characters, in a positive manner, exhibiting their habits, and the economic uses to which they might be applied, would survive the revolutions of arrangements and systems.

PERON’S PUBLICATIONS

Although Peron was now chiefly occupied with his great work, the account of the voyage, yet he deemed it expedient to detach from it a variety of separate memoirs, which he read to the Institute, the Museum, and La Societe de la Medicine.

Among these was the memoir on the genus Pyrosoma, that Zoophite so pre-eminently phosphorescent, of which we have already spoken; another was on the temperature of the sea; another on the petrified Zoophites which were found in the mountains of Timor; and others on the dysentery of hot climates; on the Betel; on preserving the health of seamen; on the localities of Seals; and on the strength of savages when compared with civilized men; lastly, he undertook a complete history of the Medusa, concerning which, he had made many observations, and of which he collected a number of new species.

In due time, the first volume of his “Voyage aux Terres Australes” appeared, after being long delayed by the plates, and an opportunity was then afforded of judging of Peron’s merits. We find it distinguished by the most scrupulous accuracy with regard to facts, a merit of primary importance in works of this kind. The descriptions of the soil and climate, and the meteorology, present phenomena which are extremely curious; and the comparison of our author’s views with those of previous voyagers, often lead to general results. The sketches of the wandering tribes of New Holland, and those inhabiting Van Dieman’s Land, make us acquainted with two races of savages of shocking ferocity, and expose the limit of the misery and degradation of the human race. No voyager, with the exception of Mr George Forster […] has been so successful in seizing the physical and moral qualities which distinguish different tribes, and in marking the connection between their organization, manners, intelligence, and numbers, and the resources which their soil afforded them; and if Forster’s narrative is superior, from the excellence of its style, our voyager has the advantage of being free from every systematic bias, and has withheld from his sketches the colouring of romance.

Peron lived to finish only the first half of the second volume, which is in no way inferior to the first; his sufferings not preventing him from proceeding to the last with undiminished care.

Our indefatigable author had also made some progress in another work of more than ordinary magnitude and importance. This was a comparison of the different races of mankind. He had collected observations on this point from every traveller and physiologist, and had himself examined the natives of the Cape, of Timor, and those of New Holland and Van Dieman’s Land; his design being to present a philosophical history of different nations, considered in their physical and moral constitution.

He proposed, vainly as it proved, not to publish this work, which had been the subject of his thoughts since his first starting, till after he had made three other voyages; one to the northern parts of Europe and Asia, a second into India, and the third to America: to devote fifteen years to this task did not appear to him too great a sacrifice; the plan was formed, the various inquiries were arranged, and he unceasingly occupied himself in finding the answer to the proposed problems. He had prepared several memoirs on this subject, which he consigned to oblivion, because they were not free from error. The fragment which contains the history of the natives of Timor is the only one nearly finished, the figures which were to accompany it, having been designed on the spot.

His portfolios included also a description of the quadrupeds, birds, and fishes he had met with, and especially of the invertebral animals, whose history he had undertaken, and of which his friend had made more than a thousand drawings. These animals still exist in spirit of wine; the drawings were executed from the recent animals; and M. Lesueur, who assisted in collecting them, could supply much information concerning their habits, and their mode of life.

For a systematic analysis of the different memoirs which Peron read to the Institute, and other learned bodies, and an exhibition of the new facts and the important results which these papers contain, we refer the student to an eloge in the 7th vol. of Mem. de la Soc. d’ Emulation, wherein M. Alard has per formed the task in a manner that admits of no improvement.

With regard to his moral character, Peron not only gained the esteem and friendship of those with whom he associated, but also acquired an extraordinary ascendancy over them. He was also most disinterested and generous. The minister conceiving that his small pension was altogether insufficient for his requirements, wished to appoint him to some lucrative and honourable post. ” Sir,” he replied,

“I have devoted my life to Science, and no bribe would tempt me to spend my time in other pursuits. If I had an office I should discharge its duties, but I am not at liberty so to dispose of myself.”

When he was entrusted with the preparation of the account of the voyage, he betook himself to a small apartment near the Museum, along with his friend Lesueur, and there lived almost penuriously, with the sole object of increasing the comforts of his family.

ILLNESS AND TRAVELS TO NICE

Meanwhile, his pectoral complaint made fearful progress, he suffered severely from it, and his cough and fever never left him. He soon came to the conviction it was incurable; and that it was useless to take care of himself, or to cease from his arduous labours. Being urged, however, to go to Nice, he thought it his duty to comply, and the journey and climate, for a time, checked his malady.

Upon this he immediately recommenced his labours with fresh ardour. He went out to sea in an open boat, and spent whole days on the water collecting mollusca and fishes, prosecuting those inquiries to which he was devoted; and it was only that he might not distress his inseparable friend, that he would ever retreat from the rain and cold, to which he frequently exposed himself. The letters he wrote from Nice were absolutely enthusiastic; he painted in the liveliest colours the joys imparted by the study of Nature, and was altogether inebriated with some discoveries he had made. But, after all, he was conscious the tide of life was fast ebbing; he rejoiced he had obtained a few months respite, and he so improved them, that the collection he there made was extremely valuable

DEATH

On his return to Paris, Peron’s health became worse than ever, and he had now no hopes whatever of his restoration. He anticipated his approaching end with surprising tranquillity, and retired to the place of his nativity to finish his days. He bid a last adieu to his friends at Paris, a duty most painful to himself, and to them. From an opinion entertained of the sanatary virtue of a cow-house, his bed was prepared in a building of that description, which belonged to an old school-fellow and friend, and where every comfort was supplied. When he required nourishment, his sisters, or his unwearied friend, milked the cows, and gave him the warm milk, which he took with pleasure. He was now surrounded by those who were most dear to him; and disentangled from all thoughts of his reputation, he often said that his last days were the happiest of his life. His friend read a great deal to him, which afforded him gratification. Every thing like irritability and impatience had now disappeared, and his reflections for the future were much engaged about those he left behind. In these circumstances his strength rapidly declined, and he breathed his last on the 14th December 1810, another proof that Science has its martyrs, and that its surest victims are often its most ardent and successful votaries.