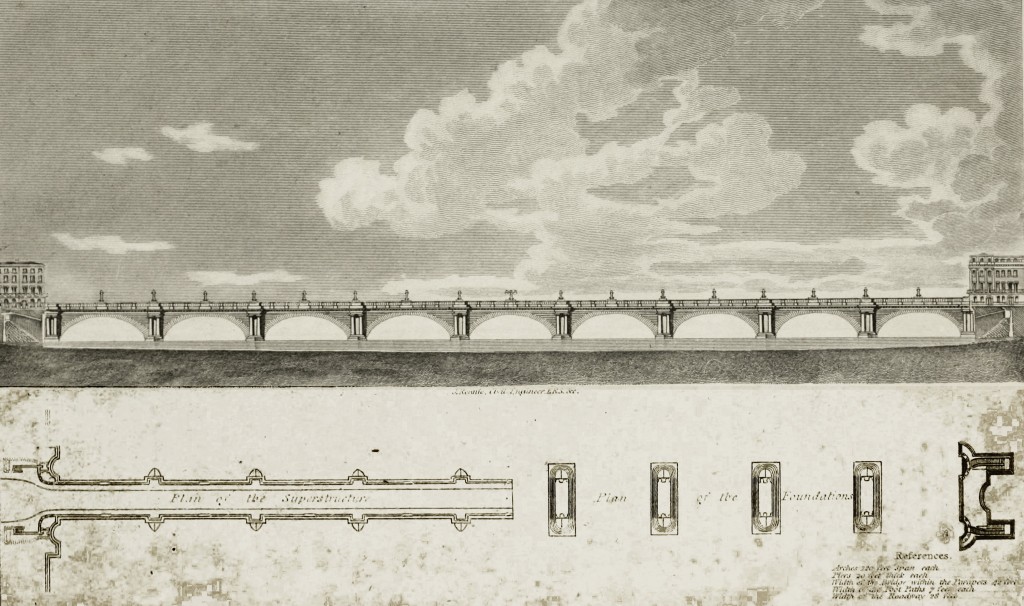

London View: Savoy from the Strand Waterloo Bridge circa 1816

[The following is the description of the above plate and reprinted from Ackermann’s Repository in 1816 as it appear/without edits. Waterloo Bridge as known as Strand Bridge prior to its opening]

It must be obvious to every reader, that the subject of the annexed engraving has been chosen for our present number, not for the beauty or picturesque effect of the buildings represented in it, but on account of the alterations which this part of the metropolis is about to undergo, and which, at no very distant period, will render a delineation of its present appearance an object of curiosity. It is well known that the few remaining vestiges of ancient grandeur, together with the modern heterogeneous erections, will shortly be swept from this spot, to make room for the splendid improvements embraced by the plan of the magnificent bridge now nearly completed.

The precinct of the Savoy derives its name from Peter Duke of Savoy, uncle to Eleanor, queen of Henry III. to whom that monarch granted the site of it, to hold to him and his heirs, upon the tenure of their delivering yearly at the Exchequer three barbed arrows for all services. Here, about 1245, that prince built a large house, which he afterwards gave to the friars of Montjoy, of whom it was purchased by Queen Eleanor for her son Edmund Earl of Lancaster. By his son Henry it was rebuilt, about 1328, in a very magnificent manner, at the expense of 52,000 marks. In 1358 this edifice was assigned for the residence of John King of France, after he had been taken prisoner at the battle of Poitiers. Here too he died in 1304. He was a prince of the strictest honour; for, after his release in the preceding year, he returned to apologize for the escape of one of his sons whom he had left as a hostage for the performance of certain treaties.

In 1381, when the Savoy belonged to John of Gaunt, it was entirely destroyed by the insurgent rabble under the direction of Wat Tyler, who set fire to it in several places. The rebels issued a proclamation, that no person should convert any part of the rich effects to his own use, upon pain of death, and actually threw into the tire one of their companions who had reserved a piece of rich plate. Having afterwards found some barrels, which, as they imagined, were filled with gold and silver, they threw them

also into the flames. The contents, however, proved to be gunpowder, which blew tip the great hall and destroyed several houses. As an appanage of the dukedom of Lancaster, the Savoy became the property of Henry VII who began to rebuild it with the design of forming it into a hospital for one hundred distressed people. He says in his will, that he intended by this foundation

to doo and execute vi out of the vii works of pitie and mercy, by meanes of keping, susteyning, and maynteyning of commun hospitallis; wherein if thei be duly kept, the said nedd pouer people be lodged viseted in their sickness, refreshed with mete and drinke, and if nede be with clothe, and also buried, yf thei fourtune to die within the same; for lack of theim, infinite nombre of pouer nede people miserably daillie die, no man putting hande of helpe or remedie.

This design was continued and completed by his son. The walls of this building, which

was in the form of a cross, are still entire. Weaver informs us, that over the great gate was the following inscription: —

Hospitium hoc inopi turba Savoia vocatum

Septimus Heuricus fundavit ab imo solo

The hospital was founded for a master and four brethren in priest’s orders, who were to officiate in turn and stand alternately at the gate of the Savoy; and if they saw any person who was an object of charity, they were obliged to take him in and supply him with food. If he proved to be a traveller, he was entertained for one night, and furnished with a letter of recommendation and as much money as would defray his expenses to the next hospital. This institution was suppressed in the 7th year of Edward VI when its revenues exceeded 500l per annum, and the furniture was given to the hospitals of Bridewell, St. Thomas’s, and others. It was restored and very liberally endowed by Queen Mary, whose maids of honour, with exemplary piety, furnished it with all necessaries; but was again suppressed by Queen Elizabeth.

Few places in London, says Malcolm, have undergone a more complete alteration and ruin than the Savoy hospital. According to the plates published by the Society of Antiquaries in 1750, it was a most respectable and excellent building erected on the south side, literally in the Thames. This front contained several projections, and two rows of angular, mullioned windows. Northward of this was the Friary, a court formed by the walls of the body of the hospital. This was more ornamented than the south front, and had large pointed windows and embattled parapets lozenged with Hints. At the west end of the hospital is the present Guard-house, used as a receptacle for deserters, and quarters for thirty men and non-commissioned officers. This is secured by a strong

buttress, and has a gateway embellished with Henry the Seventh’s arms, and the badges of the rose and portcullis, above which are two windows projecting into a semi-hexagon. The descent from the Strand is by two deep flights of stone steps.

Part of the old palace, which was used as barracks for the Guards, was destroyed by fire in March 1776. Other parts of it, still standing, have been long transformed into private dwellings and warehouses.

The ancient chapel belonging to the hospital was dedicated, with the latter, to St. John Baptist; but when the old church of St. Mary le Strand was destroyed by the Duke of Somerset, the inhabitants of that parish repaired to this chapel, which thence received the name of St. Mary le Savoy. It is entirely of stone, and has the appearance of great antiquity. The roof is remarkably fine, flat, and covered with small elegant compartments cut in wood, and each is surrounded with a neat garland and shields containing emblems of the Passion. In the chancel are some handsome monuments, among which that in memory of the wife of Sir Robert Douglas, who died in 1612, merits notice. The lady, dressed in a vast distended hood, is but a secondary figure, and is placed kneeling behind her husband, who appears in an easy attitude, reclined and resting on his right arm, the other hand being on his sword. He is represented in armour, with a robe over it; on his head a fillet, with a bead round the edge; and upon his arms the motto. Toujour sans taches. Another fine monument of a recumbent female, representing Arabella Countess dowager of Nottingham, also attracts notice. In a pretty Gothic niche, probably occupied in former times by the image of the patron saint, is now the figure of a kneeling female, holding a skull in her hands. It commemorates Jocosa, daughter to Sir Alan Apsley, lieutenant of the Tower; first wife to Lyster Blunt, Esq. and afterwards of William Ramsay, Earl of Dalhousie, who died in 1663. Within these walls likewise repose the remains of Anne Killegrew, who died, in 1685, and whose extraordinary talents were the admiration of the wits and scholars of her time.

This chapel was completely repaired in 1721, at the expense of George I who also surrounded the burial-ground with a strong brick wall; and it was again repaired and beautified a few years since. The precinct is extra-parochial, and the right of presentation to the chapel is vested in the commissioners of the Treasury.

At the eastern extremity of the Savoy is a commodious chapel for German Calvinists; and near the square at the other end, a chapel for Lutherans of the same nation. The latter was built under the direction of Sir William Chambers and is considered one of the most

elegant modern structures of the kind in the metropolis.