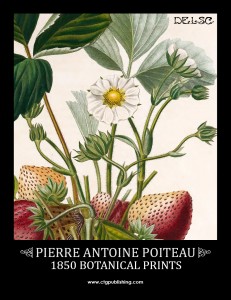

Pierre Antoine Poiteau Biography

The source of information for this biography is from the French article by François Hérincq as it appeared in L’Horticulteur français in 1872. The full CTG publication with botanical prints is available through amazon.com and scribd.com.

The source of information for this biography is from the French article by François Hérincq as it appeared in L’Horticulteur français in 1872. The full CTG publication with botanical prints is available through amazon.com and scribd.com.

Pierre Antoine Poiteau was born the 23rd of March, 1766, in the village of Âmbleny close to Soissons (Aisne). Although his father was poor and did not know how to read or write, he believed in education and sent his son, at the age of six, to study at Viviers school. The school cost 20 cents per month and 48 cents per year. It is uncertain what Antoine learned during these years.

After his first communion, his father thought him of the proper age to introduce him into his trade as a thresher. His son did not adapt well to the life of hard labor and soon became gravely ill. After recovering, Poiteau became a lemonade boy at the cafe of Noyon for a year and then returned for a second attempt at his father’s trade. This soon resulted in a decline in his health and his father realized that this would not be a suitable profession for his son.

The priest of Viviers obtained a position for Poiteau as a choir boy and gardener’s apprentice at the convent des de-moiselles de Saint-Denis for 20 écus, about 100 francs. After two years of apprenticeship, he took a position for 100 francs as a gardiner with lady Hasard, a widow of a forestry official (gard-marteau) for the forest of Villers-Gotterets. Unable to advance, he left for Paris but soon found his savings depleted and returned to Villers-Gotterets where he found work for 20 cents per day.

He then took several positions, first at a convent in Soissons and then in Saint-Paul for about 150 and 200 francs. Although he had held the title of Chief Gardener, he knew that his knowledge of gardening was not what it should be and he wished to perfect his art.

He once again returned to Paris and found work as a farmer for 18 francs a month plus 18 cents on Sundays. The year was 1789, Poiteau was 23 and the French Revolution was just starting. Three months later, Poiteau was without a job since his employer did not keep farmers through the winter season.

During this period, it was hard to find work as a gardener and so he briefly worked as a polisher at the mirror factory of faubourg Saint-Antoine. A few months later he became a gardener at the pharmacy school. During this time became resolute to obtain a position at the Jardin des Plantes of Paris but was refused the first time. He made a second attempt armed with a recommendation of Lemonnier, Louis XVI’s royal doctor, and was accepted.

He wrote to Poiret that his original intention in securing his position was to learn only the names of the plants but soon found himself learning about the plants themselves. He writes about the shortcomings of his education — no knowledge of Latin or grammar and his little knowledge of French.

“Mon intention,” écrivait-il à Poiret, “en sollicitant un emploi dans ce jardin, n’était pas d’apprendre à connaître les plantes, mais seulement leur nom; car je n’avais encore nulle idée de la botanique. Mais mon naturel studieux ne voulut pas que je m’en tinsse aux seuls noms des plantes; il voulut que je les étudiasse en elles-mêmes. C’est alors que, pour la première fois, je connus de quel prix est l’instruction. Loin de savoir le latin, je ne savais même pas deux mots de français, et je n’avais jamais entendu parler de la grammaire.”

Poiteau was offered an appointment by M. Thouin to a government’s expedition to La Peyrouse. The appointment was for 600 francs. He was overjoyed since he could dedicate himself entirely to the study of plants. He told Paillet, a professor at the college of Versailles, about his appointment and Paillet was candid with Poiteau about what the position entailed and his shortcomings, including his inability to speak his own language.

Poiteau was ashamed by his lack of education and so, at the age of 25, threw himself into the study of French and Latin while he continued to work. He kept his books near him at all times, reading with one hand and eating with the other. He referenced the books during breaks and recited words and conjugated verbs while watering.

“Je tenais mon rudiment d’une main,” dit-il dans la notice qu’il adresse à l’auteur de l’Encydopédie méthodique, “tandis que je prenais mes repas de l’autre. Quand je labourais la terre, il était toujours dans ma poche, et je l’interrogeais toutes les fois que la fatigue du travail me forçait à prendre haleine. En portant mes arrosoirs, je déclinais des noms, et je conjuguais des verbes. Bientôt je passai mes soirées à traduire à coups de dictionnaire; enfin j’entendis quelques mots du Systema vegetabilium.”

This self-education took about 8 months but he was rewarded with an appointment as the director of the fruit trees for the museum. In 1794, Thouin recommended him to create a garden at Bergerac (Dordogne). Unfortunately, the project was not funded and Poiteau, having left his post at the Jardin des Plantes, found himself without a position or resources. He entered the army of Pyrenées-Orientales but was again without a job after the war with Spain ended in 1795.

In 1796, Thouin appointed Poiteau to the expedition of Saint-Domingue. He was employed to study the vegetation of the island. He left for Rochefort but was imprisoned in Bordeaux as a suspect but was soon released because of intervention of an officer he knew from his service in the Pyrenées army. He finally arrived in Rocheford but Thouin had left no commission or authorization to board. He received his authorization on the evening of the departure and boarded with no provisions other than the 24 cents in his pocket.

It took 35 days for the boat to arrive in Saint-Domingue at Cap français. Upon his arrival, he was unable to find a place to sleep and so camped out under the government’s palace where he was discovered by an aide and detained. He was released in the morning and, after explaining his predicament, was given some breakfast and enough money to remove his baggage from the boat. The expedition’s agents could not agree on what to do with him, declared his mission useless and refused him any resources.

For two months he received patient rations from a hospital. Poiteau did not discourage and soon found an opportunity with the commissioners of the government who decided to open a botanical garden to instruct children on the elements of agriculture. Poiteau was named as the gardener. For five months he labored. His health gradually declined as well as his spirits as none of the letters that he rote to the Museum of Paris (Jardin des Plantes) were answered. He felt abandonned by the world and soon found himself hospitalized.

Upon his recovery, he gained employment as a laborer in order to eat. His fortunes changed when General Hédouville arrived in Saint-Domingue and, after learning of his predicament, hired him at 25 gourdes per month with the promised of a fixed appointment. This is when Poiteau also learned, as he communicates in a letter to de Jussieu, about the value of illustration in botanical studies. Since he believed that you are never to old to learn, he began to illustrate plants.

“Je me livrai donc entièrement à la botanique,” dit-il dans une lettre à M. de Jussieu, “mais je compris bientôt combien l’art du dessin est until à celui qui, comme moin, n’a pas l’art de s’exprimer avec cette précision que l’on voit partout dans vos ouvrages. D’après mon principe, que l’on n’est jamais trop vieux pour apprendre, je me mis à dessiner et à faire marcher de front l’étude du dessin et la description des plantes.”

This is where Poiteau also met Turpin, another botanical artist. Poiteau taught Turpin about plants and Turpin taught Poiteau about illustration. Their friendship lasted a lifetime. This friendship produced some of beautiful and important works in the botany.

General Hédouville left Saint-Domingue. Poiteau found work as an illustrator for military engineer but, with the political instability, he soon found himself imprisoned by the orders of Toussaint Louverture. He was granted passage to the United States by Dr. Stevens, General Consul to the United States.

In 1801, after five years of being in Saint-Domingue, he arrived in France with his precious collection of plants and seeds which he brought to the Museum of Natural History who had never responded to any of his letters.

In 1807, he collaborated with Turpin on Histoire des arbres fruitiers but continued the work on his own from 1837 to 1847 under the name of Pomologie française.

In 1815, he was named as the gardiner of Versailles and, in 1817 gardiner for the park of Fontainebleau. Soon after he was named as the botanist to the King and director of royal culture and habitation in French Guyana. He held the post in French Guyana for about four years and left abruptly after an argument with the director of the regions.

In 1818, he published with Risso Histoire naturelle des Orangers.

In 1820, upon his return to France, he published botanical works which elevated him in the scientific community.

In 1826, he became a collaborator of the Dictionnaire d’Agriculture d’Aucher-Eloy and of the journals le Cultivateur and au Bon-Jardiner.

In 1828, he became the editor of the annual reports for the Société royal d’horticulture from 1828 to 1848 and, in these publications, he published his Cours d’horticulture. The Société royal d’horticulture is the only pension that Poiteau earned in his lifetime.

In 1829, he became the Chair for the Horticultural Institute of the Seine region until the overthrow of the French government in 1830. He then returned to writing and botanical illustrations.

In 1829, he founded the first French journal of horticulture, Revue horticole.

Poiteau died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the 27th of February, 1854.