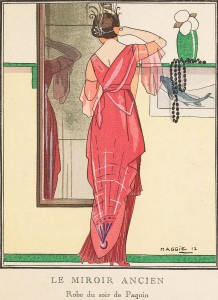

Jeanne Paquin Portrait and Biography

BORN: 1869

DIED: 1936

HUSBAND: Isidore Paquin (born Isidore Jacob m. 1891 d. 1907/1908)

BUSINESS: Maison Paquin created in 1890/1891

[the below is republished from Makers of new France by Charles Dawbarn. Published 1915 by Milld & Boon, limited in London]

Madame Paquin, with her fresh complexion, black patch, and lock of grey hair setting off the soft oval of her face, looks as if she had just stepped from the frame of some eighteenth-century painter – Gainsborough or Lawrence or Vigee-Lebrun – some one who knew how to paint beautiful women. Yet, in spite of her air of elegance, she is an intensely keen, practical woman, managing a great house of business in the Rue de la Paix. It is true that she is aided by her brother, M. Joire, but it is an open secret that she is the guiding spirit of the enterprise, with its twelve hundred employees and its branches in London, New York, and Buenos Ayres. If, in the flowing lines of her costume, the delicate shading of her hair, the grande dame manner, she recalls the mellifluous period of ruffles and buckle shoes, her active and indeed strenuous life belongs to the twentieth rather than the eighteenth century. I know no one more imbued than she with the idea of progress. She is indefatigable in her search for perfection. With the amazing energy of a Sarah Bernhardt, she is capable, like her, of lunching at four o’clock and dining at ten in the midst of great occupations. Edison’s test for an assistant is that he should forget his meals in his zeal for the laboratory; Mme Paquin would certainly satisfy that requirement.

Probably she would have undermined even her robust health, were it not for her mother, who watches over her, solicitous for her comfort and happiness, as if she were still a small child. Fresh- looking, with eyes of blue – blue like the Lake of Killarney – this devoted woman resides with her daughter, in her beautiful flat in the Rue de Presbourg, near the Arc de Triomphe, overlooking a pleasant garden and verdant lines of avenues radiating from the Etoile. I fancy she has no particular opinion of Parisiennes, except of this one, born, by the way, at the gates of Paris, at St. Denis, the burial-place of the kings of France; for the society mother of to-day either spoils or neglects her children, according to her view of it. Born in the Berry, on a great farm, she has the quiet tastes of the country, with little sympathy for the hothouse plant. She herself grew and flourished as grow the ferns on some hillside. Mother of five by two husbands – the first was a doctor and Mme Paquin’s father – she brought up the children herself. Her family consisted of six, for to her own offspring was added a little cousin, adopted principally because there was no one else to adopt her. And to all she gave a trade, so that they might be independent if the necessity arose. That is how Mme Paquin learnt dress-making as a girl. When she had the happiness to meet M. Paquin, the two went into business together, and together they mounted the ladder which leads to reputation, to a town house, to a charming villa at Deauville, to anything and everything.

It has led, certainly, to the red ribbon that gleams on the corsage of the best known couturiere in the world. “The idea of decorating a dressmaker!” the superior person cries. “What has the Legion of Honour, which Napoleon founded for his heroes and distinguished civilians, to do with her ?” But Mme Paquin, certainly, has as good a right to wear the Order as any civilian, for by her industry and talent she has benefited the nation as well as her particular profession. She has spread abroad a taste for French art and elegance as much as any writer or actress. That is why I feel justified in placing her in my gallery of Makers of France.M. and Mme Paquin brought youth and high hopes, some technical skill, and £6000 in cash to the business in the Rue de la Paix, which they founded five-and-twenty years ago. The moment was propitious. The war had come and gone and left a wreck behind. But the country was too vital to remain long under its depressing influence. On all hands were signs of revival, and in these buoyant circumstances the little barque was launched. Industries de luxe, for which Paris has long been famous, were the last to rise to prosperity. Nor was it surprising that people should restrict their expenditure on superfluities in times of national distress; such a market is more sensitive to unfavourable conditions than any other. The two young people – she was nineteen and he was twenty-four – set to work to profit by this movement; he had given up a bank manager-ship to become a dressmaker.